Back in April 2012, former British Army Force Research Unit (FRU) soldier Ian Hurst, aka ‘Martin Ingram’, phoned the retired British Army GOC in Northern Ireland, General Sir John Wilsey at his home in Devonshire and, pretending to be a television journalist, interviewed him at length about the IRA double agent, Freddie Scappaticci, code-named Steak Knife.

Hurst had for some years been campaigning to expose Scappaticci’s activities largely on moral grounds, arguing that the British state had effectively sanctioned murder by allowing the IRA agent to participate in the execution of alleged informers.

Hurst discovered Scappaticci’s role by chance when on duty in the FRU office one night when the phone rang. On the other end an RUC constable said a drunk driving suspect had given them the FRU’s phone number after he was arrested with a request for help. He checked the files and discovered the truth.

The British Ministry of Defence took Hurst, who used the pseudonym ‘Martin Ingram’ in his dealings with the media, to court in a bid to silence him. His home was also burglarised and research material stolen. The MoD also won a court injunction forbidding Hurst from publicising the code name ‘Steak Knife’. Hurst then began referring to Scappaticci as ‘Stakeknife’, a ruse copied by the media.

Wilsey was GOC between 1990 and 1993 and personally met with Scappaticci to assure him that he would be protected from the Stevens inquiry, then probing links between the security forces in Northern Ireland and Loyalist paramilitaries. Describing him as ‘our best agent’, ‘the golden egg’ and ‘the military’s most valuable asset’, Wilsey confirmed that Scappaticci was the British spy working for the FRU with the codename Steak Knife.

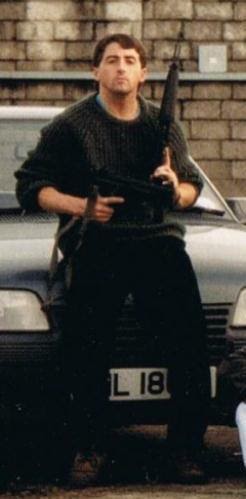

Scappaticci’s job in the IRA was as one of its spycatchers. He tracked down British agents in the IRA’s ranks, helped to interrogate and extract confessions from them and finally could be, and was involved in killing them.

Wilsey admits that he knew this and one reading of his answers suggests that Scappaticci was allowed to kill by his handlers. ‘Well, the argument is that you balance the good with the bad, didn’t you?’, he says.

Wilsey also claimed that the job of the FRU was to pass on intelligence provided by Scappaticci to MI5 and the RUC who acted on it: ‘I was responsible only for feeding them, administering them and promoting them and preparing with them…’

Wilsey is extraordinarily, even foolishly frank in his conversation with Hurst. He makes no effort to check Hurst’s identity and reveals highly secret information almost without thought. At one point Hurst asks him who the head of MI5 in Northern Ireland was during his tenure as GOC and his answer is mortifyingly frank: ‘Well, I don’t think I better tell you. Well, his name is Colin Powers.’

Full marks to Ian Hurst though. A wonderful performance from an intelligence pro.

Transcript of telephone call 1. 11 PM, Saturday, 14 April 2012

General Sir John Finlay Willasey Wilsey GCB, CBE, DL being interviewed by Jeremy Giles.

**************************************************

00:01 Speaker 1: Hello?

00:01 Jeremy Giles: Hi. Can I speak to General Jones please, sir?

00:04 S1: Who’s speaking?

00:05 JG: My name’s Jeremy Giles.

00:07 S1: Hello there.

00:08 JG: Good morning, sir. I spoke to your wife this morning.

00:11 S1: Right.

00:13 JG: I tell you what it is, sir. Andrew Vallance gave me your details.

00:17 S1: Who did? Sorry?

00:18 JG: Andrew Vallance, the D-Notice.

00:21 S1: Right.

00:23 JG: I tell you what it is, sir. We’re doing some research on a program for Channel 4 and we’ve got some documents which feature you. And really, I was wondering whether I could come down and see you?

00:38 S1: Oh, right. So you’re a television program or journalist or something like that, are you?

00:42 JG: Yeah. I’m a journalist, sir. Yeah.

00:44 S1: Right. And the…

00:44 JG: That’s how we got a hold of Andrew Vallance, he’s the Chairman of the D-Notice committee.

00:49 S1: Oh, I see. Yes.

00:51 JG: And basically, the quite serious matters were… There are documents but there’s also recording of you admitting to be in a car with Fred Scappaticci.

01:08 S1: I was in a car with him?

01:09 JG: Yeah, inSouth Belfast. And it’s recorded in some contact forms that we have.

01:15 S1: That doesn’t sound right to me. I don’t know Fred Scappa… Who is he?

01:23 JG: You don’t know who Fred Scappaticci is?

01:25 S1: No, not by that name. No.

01:28 JG: Well, you know him as “Steak Knife”.

01:30 S1: Oh, that chap. Yes, sorry. Yes, yes, yeah.

01:33 JG: Yeah.

01:34 S1: Yeah.

01:35 S1: The point of that being…

01:36 S1: But I’ve never been in a car with him.

01:37 JG: Sorry?

01:38 S1: Never. I’ve never been in a car with him.

01:40 JG: Yes. You had… Well, you were on the outside of a car but you had a meeting in South Belfast in 1993.

01:49 S1: Right.

01:50 JG: Is that right, sir?

01:53 S1: Well, this is all teen ger stuff, isn’t it? I mean, Fred Scappaticci…

01:56 JG: It is sir but what I’m saying is, before I come down, I just wanted to give you the opportunity of either saying “yes” or “no.” And clearly, there is a recording of you discussing this with another journalist fairly recently.

02:13 S1: Right.

02:14 JG: And what I don’t want to do, sir, is to mislead you. I just wanted to be clear as to the reasons why, if you allowed me to come down… It wouldn’t be on camera but I’d like the opportunity of showing you some documentation. As you know, the Force Research Unit, they produce the contact forms and they record that you were concerned you would be subject to some interest by Lord Stevens.

02:43 S1: Oh, right. Yeah, the Stevens thing. Yes, yeah.

02:45 JG: Yes. And that was your concern as to your motivation why you made that meeting with Mr. Scappaticci?

02:53 S1: Well, yes. I mean… What happened is the Head of the Intelligence in Northern Ireland came to see me and said that Stevens was burrowing around and that Fred chap, whatever his name is, Steak Knife, was unsettled and would I go and see him and reassure him to the value of his work.

03:15 JG: Yes. No and…

03:17 S1: And that’s what I did, but I never went in a car with him.

03:20 JG: No, but you were on the outside… You were in South Belfast, if I understood.

03:23 S1: Yeah. Yes. Well it took place in Belfast. Yes, yeah.

03:26 JG: Yeah. What I understood was and from what I gathered from the documents was that there was only you and him together and…

03:37 S1: That is correct. Yes.

03:38 JG: Yeah, I mean that’s how I understood it, sir.

03:40 S1: Yeah.

03:41 JG: I mean the detail, I don’t think is… How can I put this? I don’t think it’s of such gravity that it would never get in a TV program.

03:54 S1: I wouldn’t have thought so. I mean, he was outed by Stevens, wasn’t he?

03:57 JG: Well he was, sir. Yeah, I mean there’s…

04:00 S1: I thought it was the most terribly unprofessional business but he was outed by Stevens. Yeah.

04:05 JG: Absolutely. And by the way, I did read your book as well, sir, and I was looking at the references to narrow it down.

04:10 S1: And I didn’t mention his name in the book at all.

04:13 JG: No, I noticed that. So that’s why I was going to ask you because clearly, that was… Your roster details would’ve featured, I would suggest, quite prominently given that your period, your tenure, was a very political moment…

04:28 S1: Yes. Yes, absolutely.

04:29 JG: When the peace process was taking some hold.

04:33 S1: Yes, absolutely.

04:34 JG: And given Mr. Scappaticci’s role, clearly, it would be extremely unusual for a GOC to get in a car with an agent and it must’ve been a very serious situation for that to have happened.

04:51 S1: Well see, I’ve explained the seriousness of the situation: He was fed up with Stevens. He was worried about Stevens.

04:59 JG: No. I appreciate that sir, but there must be, and I don’t say there must be, but there would have been other agents who would have been concerned about things like Brian Nelson, Stevens, but you wouldn’t have got in the car with any other agent. It had to be a serious situation for that…

05:19 S1: Well, he was our best agent, as you know.

05:22 JG: Yes. I understand that, sir. Would you have been able to reassure him? Would that have been the outcome?

05:30 S1: I did reassure him. Yes, yes.

05:32 JG: And did he then go on to continue in his work?

05:35 S1: Well, as far as I know, yes. Because I never so who the product was. You would just see these intelligence reports.

05:41 JG: Yes, sir.

05:42 S1: They didn’t name the so-and-so said.

[chuckle]

05:45 JG: Yeah. And I mean I appreciate that, sir. On the contact forms that we’ve seen, it clearly does demonstrate or detail your involvement, but it’s a contact form, so if it actually does detail the agent’s name and welfare and all those sorts of issues, but any product which is generated clearly doesn’t.

06:10 S1: Exactly. But I don’t know whether… As far as I know, because I spoke to the man who asked me to go and see him. I spoke to that man later and he said, “Oh yeah. No, he’s fine. He’s much reassured.”

06:21 JG: Good. Okay, sir. That’s just fine. Can I just… I’m happy with the Scappaticci sir.

06:26 S1: Yes, of course.

06:28 JG: And we can deal with that separately, if that’s okay with you.

06:30 S1: Yeah, of course.

06:33 JG: The book, your book sir, when it deals with issues when you were, I think you were a company commander, were you during at the time of Narrow Water?

06:42 S1: In North Belfast. I was a CO in South Armagh, and that’s Warrenpoint your talking about, isn’t it?

06:49 JG: It is, sir, yeah. I always…

06:51 S1: I was the CO. I had been until two weeks previously. No. Sorry. I was the incoming CO in South Armagh.

07:02 JG: You were the incoming CO.

07:04 S1: Yes.

07:05 JG: Had you actually taken up position? Or…

07:06 S1: No, not yet. No. I hadn’t, no.

07:09 JG: Were you on a handover?

07:10 S1: No. It was the August Bank holiday, if I remember rightly.

07:13 JG: But you weren’t in theatre?

07:15 S1: I was not in theatre, no.

07:17 JG: Where were you at that time, sir?

07:19 S1: I was commanding my regiment.

07:21 JG: In the UK?

07:22 S1: In Colchester.

07:24 JG: Okay, sir. Can I ask you a question then, sir?

07:28 S1: Of course.

07:28 JG: When you come into theatre, as the CO in…

07:33 S1: In South Armagh.

07:34 JG: Were you on a roulement detachment then?

07:35 S1: In South Armagh, in Bessbrook Mill, yeah.

07:38 JG: And was it on the three-month deployment?

07:40 S1: Yes. Well, it was actually six months by then, I think.

07:43 JG: So roulement.

07:44 S1: Yeah, it was a roulement. Yeah it was.

07:46 JG: So when you come in, would you have been then aware of any concerns in regards to, what’s the word I’m looking for, whether there was any intelligence generated?

08:02 S1: Well, yes. We were always concerned about intelligence as the book states. We never used to get any intelligence and that was always the terrible disappointment thing. We never used to get any contact intelligence.

08:15 JG: You never, but as a company commander… Sorry, as the CO of a regiment, presumably you wouldn’t have received quality intelligence. You would have got the stuff that’s produced by the local unit intelligence officer.

08:31 S1: Absolutely, and also the RUC and, as my book states, the trouble was that a regiment would arrive. It would take time to get established and the police would stuff out the regiment and see whether they were competent in the way they handled things or not, and then perhaps towards the end of their time, they would drop a bit of a useful for intelligence in the pond.

08:55 JG: But you would never see FRU product?

08:58 S1: You would never see who it came from, no never.

08:59 JG: No, you would never see force research of product as the CO of that unit. Obviously, at the GOC, you saw FRU product but when you were the CO of that roulement, of that battalion in South Armagh, you would never have seen any intelligence product generated by the Force Research Unit?

09:19 S1: You never knew where they come from.

09:23 JG: You would know it was a unit, wouldn’t you? You’d know from a MISR what unit it came…

09:28 S1: No, you never saw… I never saw the MISR’s.

09:30 JG: You never saw… That’s the point that I was making, sir. You never saw FRU. All MISR’s are generated by the Force Research Unit.

09:37 S1: Yeah, absolutely.

09:38 JG: So you didn’t see any product down that…

09:42 S1: No, what would happen is if someone would arrive, a policemen would arrive or a member of the regiment would arrive and say, “We’ve got an interesting one here and we would like you to stake out Forkhill”, or something like that. And that’s the nearest we got to it.

09:56 JG: Okay, sir. And you would never have any dealings with the Garda?

10:00 S1: And we had no dealings whatsoever with the Garda, ever, ever, ever, ever.

[laughter]

10:03 JG: Even when you was a GOC, sir, you wouldn’t have had any…

10:05 S1: I had no dealings with the Garda at all. Anything that happened with the Garda would have gone through the chief constable.

10:12 JG: Yeah, I understand sir.

10:14 S1: The Garda was off limits.

10:15 JG: Can I ask you, sir, you say it was off limits, was that purely geopolitics?

10:21 S1: As I understood it was pure politics, yes. I mean, I think it probably came from the other side of the border in the sense that the Garda didn’t recognise the existence of the British Army because, of course, we were a foreign power at the time.

10:37 JG: Yes, sir. And would that have been the attitude which was, you understood, to be in place during 1990 and 1993?

10:47 S1: Absolutely.

10:49 JG: I mean, it’s different today, I suppose.

10:51 S1: It’s very different today, yes. Yeah.

10:53 JG: And who would the Secretary of State been then, sir?

10:55 S1: I had Peter Brooke and Paddy Mayhew.

10:58 JG: And would they have been supportive politically if you were to have said to them, could we have some cross border liaison?

11:08 S1: Oh, I often said, could we have some… I used to make… Of course, when I was in South Armagh, it wasn’t Paddy Mayhew and Peter Brooke. That’s was when I was GOC. I think it was Tom King probably at the time.

11:20 JG: But when GOC, clearly…

11:22 S1: When I was GOC, I had Peter Brooke and Paddy Mayhew, and I was forever saying to them, we must improve this, and of course, it was of our great frustrations. We would never improve.

11:32 JG: As a Five Star, you would presumably expect to have had some means of communication with your equivalent in the Irish set?

11:43 S1: Army, yeah. But I had none whatsoever.

11:46 JG: What would happen, sir, in this situation if you had hot pursuit for once in a better…

11:53 S1: Well, it’s a very good question. As things improved politically, they relaxed the hot pursuit rules, and if I remember it rightly, the hot pursuit was allowed by air. So the helicopter would like to fly over the border, so I think at depths of about five miles in hot pursuit. The ground troops were still not allowed to get in hot pursuit.

12:19 JG: So there is never any ground. As GOC, sir, did you ever authorise any cross border?

12:27 S1: None at all.

12:29 JG: I am talking, perhaps, not normal units. Let me put it that way.

12:34 S1: No we never did. And it was absolutely strictly taboo. It was one of the great taboos. We knew that there was any suggestion, that anyone is going across the border, there will be an uproar in Dublin and that would get to Westminster and then come down to us.

12:51 JG: You know that had been authorised previously by your predecessors.

12:56 S1: As GOC?

12:57 JG: As GOC, yeah.

12:59 S1: Well, I think that they’d have got into deep trouble about it.

13:02 JG: Well, they may have done sir, but we’ve got documentation that shows that there has been previous FRU activities which were authorised by your…

13:11 S1: Well, I think, in the early days but I think there is such a…

13:15 JG: No, that is the point that I was making.

13:18 S1: I never did it anyway.

13:19 JG: No, I’m not suggesting you did sir but what I am saying is previous GOC’s had authorised.

13:25 S1: I’m sure, yeah. There were very bad relationships at various times.

13:30 JG: Yeah…

13:33 S1: The Creasey period was…

13:35 JG: The politics.

13:36 S1: Was very bad time.

13:37 JG: It is basically politics. In the 80s, when you were down in South Armagh. That was very difficult, when there was mistrust and suspicion on both sides of the…

13:49 S1: Absolutely, and I decided that we play straight it. So we played it straight.

13:53 JG: Thankfully, sir, we are in a better position today aren’t we? I mean today its…

13:57 S1: Today, it must be March month already. Yes, I am sure.

14:00 JG: Can I ask you sir, when you… Again, the GOC, so the period 92 to 93, clearly, you wer e the GOC at that time, when Brigadier Ian Liles, produced these reports on after the Breen and Buchanan.

14:17 S1: Of course, I am inside of that, Brigadier Wild?

14:20 JG: No Ian Liles.

14:22 S1: Ian Liles?

14:22 JG: He is a Brigadier today sir. I am not sure he was a Brigadier then, but he produced a report which was shortly after the murder of the two more senior police officers, Mr. Breen and Mr. Buchanan.

14:37 S1: Mr. Breen, well, that was much earlier. I think that was in ’82, isn’t it?

14:41 JG: No, it was later on in ’89 sir, but…

14:45 S1: ’89, yeah.

14:47 JG: The report was made during your tenure, I understand.

14:51 S1: Right, okay.

14:51 JG: But I don’t know whether you remember seeing it.

14:53 S1: No, I didn’t definitely.

14:54 JG: As a GOC though, perhaps, you see thousands of documents and it might…

15:00 S1: I don’t remember seeing anything by a chap of that name, no.

15:02 JG: You don’t remember his name. That is where they are helpful, sir, because that does help me just to chart things as to who had knowledge of what points. I mean my only interest in that is to make sure that we don’t tread on a landmine by going down and having you that isn’t correct for want of a better expression.

15:26 S1: I don’t think so. I mean I didn’t clear my… I clear my book with the Ministry of Defence and I had no comments whatsoever on it. So it’s a pretty anodyne stuff, and I did not want to kick sand in the eyes of the IRA or the police or anybody else, or the republic.

15:45 JG: I think your book is a good read sir, if I may add. Did you write it yourself or did you have…

15:49 S1: I did it entirely myself. Yes.

15:51 JG: I suspect that you did sir because it has come from a very military perspective, but I enjoyed the read and…

15:59 S1: Well, I’m glad you did. It’s great, yeah.

16:00 JG: I was slightly disappointed you didn’t add the material about Mr. Scappaticci or at least why–not that the incident took place, because I understand why you did not make reference to that-but the fact that there was concerns regarding you detail what has been one of the most valuable assets.

16:24 S1: Well, you have to remember that the military background was such that we knew we had this source, Steak Knife, and it was the golden egg. It was the one thing that was terribly important to the army. So we never ever, ever mention the words “Steak Knife”, or whatever he subsequently became. I think it was 2001 or something like that.

16:54 JG: What about the police, sir, would they have had…

16:57 S1: Well, they were trying to get him off us.

17:00 JG: They were trying to pinch him?

17:02 S1: Get him off. They wanted to run him himself, you see.

17:05 JG: Okay, sir. That makes sense.

17:07 S1: And, as I explained in the book, Fred did not want to get with the police. He thought they were sectarian and he did not want to be handled by MI5 or MI6. He thought that they were whole lot of sort of university poofters and so on.

17:21 JG: And so that is the reason that you came into…

17:26 S1: So we were terribly cagey about Fred.

17:29 JG: Had he been compromised at that time sir? Or…

17:31 S1: No, he hadn’t. Absolutely, not.

17:32 JG: So he was still active within…

17:35 S1: And he was the most valuable asset and he was probably the military’s most valuable asset.

17:41 JG: And so, at that point, it was the damage limitation as that you could say. You wanted to keep him on board.

17:50 S1: When I said I was going to write my book, there was an absolute uproar about it and the first chapter, with the chapter that I wrote first was the one and I write it because I knew his handler, who is in my regiment.

18:04 JG: You mean his original handler?

18:05 S1: His original handler which is… His name is Jones and who is truly the chap I wrote about.

18:12 JG: And are we going back now to 1977?

18:17 S1: We came back to 1976-1977.

18:19 JG: 1976-1977?

18:21 S1: Yeah.We are, yeah.

18:22 JG: What regiment were you, sir?

18:23 S1: Devon and Dorset.

18:24 JG: And did Jones come from…

18:26 S1: He’s a Devon and Dorset, yeah.

18:28 JG: He did, yeah.

18:28 S1: But he was in my platoon.

18:30 JG: Was he, sir?

18:31 S1: Yeah.

18:32 JG: I didn’t know that you’re adding something…

18:34 S1: Yeah. Well, it’s in the book, you see.

18:35 JG: I did know all of them.

18:37 S1: Yes.

18:38 JG: But I didn’t know… And I knew, clearly, because the Force Research Unit didn’t come into operation till 1980.

18:46 S1: He was transferred to the Force Research Unit after he left the Devon and Dorset.

18:51 JG: What’s his first name, sir?

18:53 S1: Peter. PJ. Peter Jones.

18:55 JG: Peter Jones.

18:56 S1: Yeah. It’s all in the book.

18:58 JG: He then became Int. Corps, didn’t he?

19:00 S1: Well, he never did it. He never re-badged.

19:03 JG: He never re-badged.

19:04 S1: But he’s attached to the Intelligence Corps.

19:06 JG: Yeah. The FRU was an Int. Corps sponsored unit. But he never re-badged, did he?

19:11 S1: He never rebadged. He’s still a Devon and Dorset to this day.

19:13 JG: Was he promoted to FRU, sir?

19:15 S1: He was promoted all the way through to WOII. And he’s a very, very brave man. He got the deuce. He got the George class.

19:26 JG: Was he referred to as Paddy?

19:28 S1: No, never. No.

19:30 JG: No. Did he wear a… I mean it’s a stupid thing, sir. Did he ever wear it like a donkey jacket?

19:35 S1: I’m sure he did, yeah.

19:38 JG: That was something that was written in one of the documents which characterised one of the handlers. So would he have stayed in theatre in the ’80s, in the early ’80s?

19:50 S1: Yes, he was there in the early ’80s. Yeah, absolutely.

19:53 JG: Was he, sir?

19:54 S1: Yeah.

19:55 JG: I don’t think I’ve seen his name in the documentation that I’ve…

20:00 S1: Well, if you read chapter 4 my book, you’ll find the whole history of that.

20:03 JG: Okay. So, I didn’t read that chapter after. I admit, sir, my research has been lacking in that department. I didn’t appreciate that you dealt…

20:11 S1: Yeah. He’s a very important man.

20:14 JG: Absolutely, sir. And he’s still alive and well?

20:17 S1: He’s still alive and well. Anyway, just getting back to what I was saying, when I started to write this book, I’ve written that chapter first because he was the one who was most accessible to me because I knew him very well and I discussed it with him and he was very happy of me to write about it. Then he said, “Life got to go on. I’ve got to get a job,” and so on and so forth. By this time, of course, he was out of the army.

20:40 JG: Okay, sir. Presumably, the MOD were happy for you to write about Scappaticci?

20:48 S1: Well, the MOD weren’t happy, obviously, but they just miss the point that I was trying to make. The MOD was very anxious about it. I mean, I used to get a letter from the chairman of the D List committee who was then a chap called Nick Wilkinson, who was a friend of mine.

21:03 JG: Yeah.

21:07 S1: Nick Wilkinson.

21:08 JG: Nick Wilkinson, yeah.

21:10 S1: I used to get a letter from him.

21:12 JG: Yeah.

21:13 S1: And then, I used to say, which is what I’ll tell you, that my book was a attribute to all those who served in NI, whether they were military, or whether they were civilian, or whether whatever they were.

21:22 JG: Mr. Wilkinson would come from the same school as you?

21:26 S1: Absolutely. So he did it in it’s entirety. Anyway, then the heat went off it and I took… And because it took such a long time to produce because of the Bloody Sunday inquiry.

21:39 JG: Yeah.

21:39 S1: Well, that’s another story. The heat went right out of it. And this is my point I’m coming to, I was very conscious all the way through about the chap we called the “Steak Knife.” And I did not want to jeopardise him because I’ve grown up to the fact that that was one of our best secret and our best assets, and our most important secret.

22:05 JG: And presumably, Mr. Jones would never go to camera on matters?

22:10 S1: He would never get public, no.

22:11 JG: Okay. Presumably, you would never want to go public on this sort of thing?

22:16 S1: I wouldn’t want to get public on that sort of thing, certainly not.

22:17 JG: No. I can fully understand that. So you just touched on a point before I bid you farewell, sir, because I don’t want take too much of your time.

22:28 S1: No, it’s fine.

22:29 JG: I know it’s a Saturday.

22:30 S1: I like talking about it, yeah.

22:31 JG: I was curious as to, clearly you with GOC, again, at a very, very crucial point when Steven’s inquiry was at its early days. Stevens comes in to theatre in ’89 and Stevens One. He’s about to be wound up, isn’t it, during your period?

22:54 S1: Yes. It was. He completed his task. And, of course, his investigation was most unwelcome to the RUC.

23:07 JG: And to the army?

23:08 S1: Well, it was unwelcome to the army as well but it was unwelcome particularly to the RUC, and I remember the Chief Constable said to me, don’t’ deal with Stevens direct. He must always only deal with him through me and I was very happy to do that.

23:23 JG: Did Stevens ever meet with you, sir?

23:25 S1: Well, he did, actually. He did come to see me, yes. He came to see me because of a chap called Gordon Kerr.

23:32 JG: Pardon. Who is he, sir?

23:34 S1: Gordon Kerr, who is a CO of the FRU, I think.

23:37 JG: Okay, sir. And did he come with you?

23:40 S1: No. Stevens came to see me because Gordon Kerr had got an OBE in the New Year’s Honours list?

23:49 JG: Right.

23:50 S1: And Stevens deduced that that must indicate that my predecessor–because I wasn’t there at the time–my predecessor must have been complicit in what the FRU were doing because otherwise he wouldn’t have got an OBE.

24:02 JG: I see, yeah.

24:03 S1: And I said to Stevens, “You don’t know what you’re talking about.” People get awards for service going back for years and years and years and years. It’s not for a particular issue or a particular item.

24:16 JG: So he took that to be an indicator that…

24:18 S1: He took that to be an indication that the army, at the highest level, was complicit in what he, Stevens, thought was going on.

24:27 JG: I understand, Sir. And did he ever…

24:29 S1: So that was the only time I met him. He had no issues with me personally.

24:33 JG: Did he ever raise Scappaticci with you, Sir?

24:37 S1: No never did, no. And the next time I saw, anything to do with Stevens, was when he actually outed Scappaticci, or whatever you call him.

24:44 JG: Yeah.

24:45 S1: And I was absolutely, completely dumbfounded because a policeman protects his sources at all times.

24:56 JG: Why do you think that happened, sir?

24:59 S1: Well, I think he obviously thought that Steak Knife was guilty of some crime and that this was his vengeance on that.

25:09 JG: Do you think that he was guilty of any crimes?

25:15 S1: Well, I only heard one side of the story, that he saved hundreds and hundreds of lives.

25:20 JG: But you saw his product presumably, as GOC.

25:23 S1: Well, I didn’t ever see his product linked to his name.

25:25 JG: No, I appreciate that, sir.

25:27 S1: Ever.

25:27 JG: But you would see because of the matters which were being reported in the MISR’s and the other documents which were generated, that he was working in a very crucial, sensitive unit.

25:41 S1: I knew he was working in a sensitive role and I knew what he was doing and what his job was, and I knew that that put pressure on him enormously. But I was always told–and of course, I had nobody to check this out–I was always told that he had saved thousands, hundreds of lives I think.

26:04 JG: You clearly understand his sensitive role to be within the internal security unit?

26:11 S1: I understood that was his role. That was his final role. I mean he worked his way up through the IRA, didn’t he?

26:16 JG: He did, sir, but from the very early 1980’s, he was in the internal security.

26:21 S1: Absolutely, so that was his role.

26:24 JG: And clearly I suppose the point that I’m making sir and again, I don’t expect you to ever go in a public fashion on this point, but in the internal security unit, his job is to interrogate suspected informers. And he, in the Eamon Collins book, “Killing Rage”, he recounts how Mr. Scappaticci was involved in shooting a suspected informer. Now, clearly, you saw products, because I’ve seen some of these documents which detail his involvements in these incidents, let’s not say they are crimes because clearly a crime suggests criminal activity and if you’re doing it on behalf of the state there’s no crime. That would be the argument advanced.

27:15 S1: Well, the argument is that you balance the good with the bad, don’t’t you?

27:18 JG: That’s the point.

27:21 S1: On balance, it comes out that you’re getting more value. The state’s getting more value than it is…

27:25 JG: So in essence sir, what I’m saying is that the GOC is the person ultimately responsible in theatre for the force research unit. You were happy, or not happy that’s the wrong word, but you were confident that the profit and loss account was greater in profit that it was in minus.

27:44 S1: Well, I must correct you on something. You say the GOC was responsible. The Force Research Unit worked for MI5 and for the RUC, and all the product went to them. So I was responsible only for feeding them, administering them and promoting them and preparing with them…

28:02 JG: I understand sir. They were a force unit…

28:04 S1: They were a force unit, and they were not my unit.

28:07 JG: Yes I appreciate that sir, but in theatre, if you look at the… We’ve seen the ORBAT for the unit. And although, it is funded by direct to special services, Special Forces, and hence, the reason why they get special force pay, ultimately responsibility for that unit was tagged to GOC Northern Ireland.

28:30 S1: Only administrative, I can assure you, not operationally.

28:34 JG: No, I’m not saying operation sir, because they wrote to the operational…

28:38 S1: So I had to be satisfied that they were acting legally and within their charter.

28:45 JG: And were you satisfied?

28:47 S1: I was told always that they were.

28:48 JG: Were you satisfied they were acting legally?

28:51 S1: I was, yes, absolutely.

28:53 JG: So as the GOC, if you thought Mr. Scappaticci was involved in the internal security unit and interrogating a suspect and that person is then murdered, that would be lawful would it?

29:12 S1: No, it wouldn’t have been lawful, and it would have been something which I would have queried.

29:16 JG: And that’s the point that I’m making. So there was a fire break, was there, to your knowledge in the sense. You saw the product but you couldn’t be associated with the act?

29:27 S1: That is correct.

29:28 JG: So that act would then… If I’m right in thinking, was that done deliberately to protect the five, sir?

29:36 S1: I don’t think so, no. I think it was for security purposes, for secrecy purposes.

29:39 JG: Yeah, so people…

29:41 S1: The sensitivity was such that intelligence is held at the very, very highest level.

29:46 JG: No, I appreciate that sir, but as you know yourself, there’s always vast amounts of documentation which is generated to run an agent like Mr. Scappaticci.

29:58 S1: Absolutely.

29:58 JG: And that needs all documented in the most minute of detail, everything from the pickup routes, to the welfare, to the amount he was being paid. And all that is collected over two and a half decades.

30:14 S1: Yes.

30:14 JG: But the point that I’m making is you would never see that, would you?

30:17 S1: I would never see that.

30:17 JG: No. So indeed, presumably, and you might be able to answer this, would the Secretary of State be?

30:26 S1: I imagine the Secretary of State probably would but I don’t think either… Besides, I think the Secretary of State was, as I put in my book, he could never have known who the agent was. He would have known the code word, Steak Knife, or whatever it was.

30:38 JG: Yeah, and that’s to protect…

30:41 S1: And that is to protect him.

30:42 JG: So how is it you came into knowledge about Mr. Scappaticci?

30:46 S1: Only by keeping my eyes and ears open.

30:50 JG: No, what I mean is, when you met him.

30:53 S1: Oh, because I told you, the Head of Intelligence in Northern Ireland came to say, “We got a problem.”

30:58 JG: No, what I meant is… That’s what I mean, so the Head of Intelligence comes to you and he says, “We have a problem. Can you help me, sir?”

31:05 S1: Absolutely.

31:06 JG: I need you to have a meeting to reassure Mr. Scappaticci. Did that surprise you that he would come to in such an open way?

31:15 S1: No, because I said to him when I arrived in the job, I said, “If you ever you need any help, let me know.” I mean it’s a typical, typical, sort of general type of remark.

[chuckle]

31:22 JG: Absolutely, sir.

31:23 S1: You arrive, and you say, “Hello everybody. I’m John Wilsey. I want you to know, I’m here to help.”

[laughter]

31:32 JG: Sir, I understand exactly where you’re coming from. It’s just…

31:35 S1: And I knew their head of intelligence, they were indeed.

31:39 JG: Who was it at that time, sir?

31:41 S1: Well, I don’t think I better tell you. Well, his name is Colin Powers.

31:46 JG: Yeah, a Northern Irish gentleman?

31:49 S1: He comes from the North, yeah.

31:51 JG: Yeah, I know him, sir. Had he come back to the Force Research Unit in 1993? Because he was there…

32:00 S1: I think, he has, yes.

32:02 JG: He was there back in the early ’80s because he’s on the…

32:07 S1: What he was one who is very concerned I was writing this book, I know that.

32:11 JG: Colin Powers?

32:12 S1: Yes.

32:13 JG: And to be fair, sir. I suppose we can all understand why he would be concerned.

32:20 S1: Absolutely. No, I have no difficulty with it, but my story was… The subliminal part of my story is ta tribute is paid to all of us and he has never been paid before.

32:30 JG: Yeah.

32:32 S1: And so, for the greater good, my book tells the story of the greater good rather than the detailed analysis.

32:39 JG: Did you ever meet the handler, sir, or who was there at the time, when you met with Mr. Scappaticci, a guy called Mr. Moyles?

32:45 S1: No, I never met him. No.

32:47 JG: You never met him?

32:48 S1: No.

32:49 JG: So when you met with Scappaticci, who was present?

32:52 S1: I think Colin Powers. I think Colin Powers, probably.

32:56 JG: And just you, sir?

32:57 S1: And me, yeah. It may just been the two of us together. I can’t honestly remember.

33:01 JG: And how long did that meeting take place, sir? Just sort of…

33:03 S1: About half an hour.

33:04 JG: And that was it? And you never saw him again afterwards?

33:07 S1: Well, no, I never saw him again in Northern Ireland afterwards.

33:12 JG: But did you see him out of Northern Ireland?

33:15 S1: I’ve seen him since, yes.

33:17 JG: In what side of situation would you…

33:20 S1: Well, he had a problem and again, I said to him, “If you ever have a problem, let me know.”

33:24 JG: But how would he make contact with you, sir?

33:27 S1: I didn’t know how he made it. Probably the same way as you did.

33:30 JG: [laughter] I hope not, not through the D-notice. And his problem was because he’d been exposed?

33:37 S1: Well, it was a legal difficulty that he had.

33:45 JG: Alright, okay.

33:46 S1: And who was going to pay for it, and so and so. Who’s going to pay for legal advice and so on?

33:50 JG: Yeah. And Ministry of Defence pick up his legal fees, don’t they?

33:54 S1: Well, absolutely, but only on matters bearing on whose activity at the time.

34:01 JG: Yeah. I know his civil matters or contingency are paid separately. He asked it from them. But clearly, matters when he’s dealing with his work, I think he’s actually featuring in the tribunal in the republic at the moment.

34:22 S1: Sure.

34:23 JG: And he gets from the FRU, doesn’t he? As in…

34:26 S1: Well, I think that was the trouble. I think there were errors where he wasn’t being funded and that’s what he wanted help over.

34:34 JG: Did you know anything of this solicitor, sir?

34:37 S1: Not at all. I passed it probably onto the right quarter.

34:41 JG: Okay, sir. And they dealt with it?

34:45 S1: Well, I imagined. I never heard from him again.

34:46 JG: So he was satisfied. [chuckle] Alright, can I leave you, sir? You’ve given me plenty to think about before… Can I come back to you next week and, perhaps, at your convenience, I could come down and see you, sir, off the record?

34:58 S1: Yeah, go on. Come and see me, by all means do. I’m not taking part in any program or anything like that.

35:02 JG: No sir, I know that. I don’t expect you at all to go to cameras, sir. But it would be helpful, so we get the story, correct. I mean, clearly, as a five-star general, you would be in a very privileged position. I don’t expect you to give me any secrets that you aren’t comfortable with, but if I show you some documentation, then you can put us, either to that it’s a serious matter or it could possibly be used, and we would respect that.

35:36 S1: Okay.

35:37 JG: Is that fine, sir?

35:38 S1: Yeah.

35:39 JG: If I’ve got any questions tomorrow, sir, if I think it over today, would it be possible that I could give you a ring?

35:44 S1: Yeah, of course. Give us a ring, yeah.

35:46 JG: Alright, sir. Well, I won’t disturb your Saturday afternoon any further and hope…

35:51 S1: No, it’s nice talking to you.

35:52 JG: I hope you pick the winner of the Grand National, sir.

35:54 S1: Thank you very much. Who’s it going to be?

35:57 JG: I am a favourite man, sir, so I think I’ll be going for Ginger McCain at the Ballabriggs…

36:04 S1: Great. Okay. Nice talking to you.

36:05 JG: And you, sir.

36:06 S1: Say again your name?

36:06 JG: Thank you. Bye.

36:08 S1: Bye.

36:08 JG: Bye, Sir.

-END-

You must be logged in to post a comment.