By grotesque happenstance I had just finished re-reading Ruth First’s groundbreaking account of the Libya that was inherited and refashioned by Gaddafi – “Libya – The Elusive Revolution” – as news came through that NATO airstrikes, possibly the work of one of Barack Obama’s predator drones, had killed Gaddafi’s youngest son, Seif al-Arab and three of his grandchildren, all reportedly under twelve years of age.

And then I had just completed the first edit of this post when the news broke that Obama had killed Osama bin Laden at a compound not far from the Pakistan capital Islamabad, apparently with no foreknowledge on the part of the Pakistanis and with a degree of contempt for Pakistani sovereignty that can only serve to destabilise the government there and vindicate those who followed the al Qaeda leader’s violently anti-American gospel.

Imagine how Americans would react if Mexican special forces landed outside Los Angeles, invaded a compound to kill a cocaine king hiding out there, didn’t tell the FBI a word about their plans and afterwards, as jubilant Mexican crowds waved flags and cheered in downtown Mexico City, the country’s president went on TV to boast of the deed and house-trained Mexican journalists went on air to bad mouth American co-operation in the war against drug cartels. How long would the US government survive?

So my first thought was really a question: and they wonder why people hate them enough to fly planes into their skyscrapers? My second thought was, I confess, on the conspiratorial side. Was it possible, I wondered, that American military planners had hoped for a double whammy here, wipe out Gaddafi on Saturday and Osama on Sunday to send a message of US military hegemony throughout the Middle East and Muslim world? Who knows.

The effort to remove the Al Qaeda leader was clearly a spectacular success that will strengthen Obama’s chances of re-election in 2012 and weaken domestic opposition to his plans to cut back government spending on the poor and sick. The bid to kill Gaddafi didn’t however go at all as well.

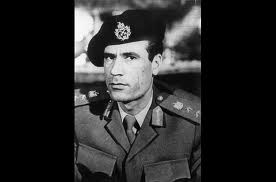

If confirmation was needed that Western intervention in Libya is really about regime change, installing a more reliable pro-Western government in Tripoli and exacting revenge on Gaddafi for his years of troublemaking and much less about protecting rebellious civilians from the Libyan leader’s vengeful retribution this effort to liquidate him was surely it.

NATO has now denied that its forces deliberately singled out the Libyan leader and claimed instead that their target was a military one, a command and control centre housed in the same building. Gaddafi’s family was an incidental target according to this version, but there’s a distinct flavor of the Mandy Rice-Davies in that response: “They would say that, wouldn’t they?”

The UN resolution authorizing military action limits NATO to protecting civilians and does not permit regime change or assassination bids on the Libyan leader or his family. If NATO had admitted Gaddafi was the target the mission in Libya would have been rendered illegal, hence the need for what many will see as the plausible but unprovable lie.

But the leadership rhetoric and military thinking emanating from Washington, London and Paris has been increasingly focussed on the goal of killing Gaddafi or coming so close to doing so it would scare him out of office. Take as an example this quote from Admiral Mike Mullen, chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, given to Reuters just after the use of predators was authorized: “Ultimately, he said, ‘Gaddafi’s gotta go’, and coalition actions ‘are going to continue to put the squeeze on him until he’s gone.’”

This weekend’s assassination bid on Gaddafi is the second strike against the Libyan leader in a week. His compound in Tripoli was targeted in late April and an office where he and his aides sometimes worked was destroyed. Western determination to remove Gaddafi seems absolute and in sharp contrast to the mild response to the murderous repression of protesters in Syria, whose brutal government’s survival is in the interests of America’s ally, Israel, or in Bahrain, where Saudi concerns dictate almost complete American passivity in the face of that regime’s murderous crushing of its citizens.

Hardly surprising then that many will see that self-interest and hypocrisy more than consideration for her citizens’ democratic wellbeing characterize the West’s disposition to the Arab Awakening in Libya. But then as far as this North African State is concerned it was ever thus. Which brings me back to Ruth First and her examination of the Libya that Gaddafi and his fellow ‘Free Officers’ took over in September 1969.

I first came across “Libya – The Elusive Revolution” in 1975, just after I had spent two years living and teaching at the University of Tripoli. The country had a great effect upon me and intrigued by the little history and politics I had learned, I wanted to know more. But we were expatriates in a country whose people and media were, for language reasons, virtually inaccessible. Our view of Libya was, to say the least, opaque.

Understandably the locals who did speak English, whether at the college or out at the farm where I lived, were very careful about what they said to foreigners and sometimes, as I learned on one occasion, with good reason. Consequently we had to rely on fellow expats for most of our information about Libya, Gaddafi and the politics of the place and a lot of that came filtered through ignorance, prejudice and plain stupidity.

So when I came across Ruth First’s account, which was published the year before I departed Libya, it was really an eye-opener. Much of what I had seen, heard or experienced while living there now made more sense and when I finally put her book down it was with a feeling of disappointment that I hadn’t known all this when I was living there, when it counted. The experience of life in Libya would have been richer.

But first a few words about Ruth First. Her parents were Latvian Jews who had emigrated to South Africa at the turn of the last century and they were founder members of the South African Communist Party. Ruth also joined the Party and at university in Witwatersrand she shared classes with a young Nelson Mandela and Eduardo Mondlane, a founder member of FRELIMO, the Mozambique liberation movement.

The South African Communist Party and the African National Congress went on to make an alliance against apartheid and together created the ANC’s military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe, the Spear of the Nation. In 1949 Ruth First married a fellow Party member, the legendary Joe Slovo, the son of Jewish emigres from Lithuania who went on to become a leading light in the ANC (their union is a reminder of the progressive and radical tradition, pre-Israel, pre-1967, pre-neocons, pre-Bibi of so many Jewish political activists).

Ruth First was immersed in anti-apartheid agitation and in 1963, when the South African authorities moved against and imprisoned ANC leaders such as Mandela, she was interned. After release she sought sanctuary abroad, mostly in Britain where she became an academic and latterly in Mozambique where she combined academic work with activism against apartheid.

In 1982 the South African police decided she was so much a thorn in their flesh that she had to die. A parcel bomb was sent to her office at the university in Maputo and she was killed instantly when she opened it. Her life story was made into a film, A World Apart which was written by her daughter Shawn Slovo. Another daughter, Gillian Slovo is a celebrated novelist.

Her study of Libya then is strongly influenced by her politics. Not in a propagandist way but by setting the country’s history and development against a background of the burgeoning Cold War, of Western colonial interests, both economic and strategic, which sometimes clashed and competed but often merged for mutually beneficial gain.

Not everyone will find this sort of approach readable or even acceptable. But in the case of Libya there really is very little choice because the place has been a plaything for foreign powers and interests for most of its existence and no attempt to understand Gaddafi or his present predicament is possible without knowing what is was that brought him to power.

The conditions that led to the coup that he and his fellow “Free” officers engineered have their direct roots in the politics of the Middle East and Cold War Europe in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Italy had succeeded the Ottoman Empire as Libya’s occupying power in 1911 and held the country until 1943 when the British defeated Rommel’s Afrika Corps at El Alamein. After the final German surrender the victorious allies, principally Britain, the US and France, with Italy accorded a bit player role, carved up the country in accordance with their Cold War and late colonial interests.

The Italian occupation of Libya was, as First described it, “the most severe….experienced by an Arab country in modern times” and this was especially so when Mussolini’s fascists came to power. Libya was deemed to be part of mainland Italy, as it virtually had been in the days of the Roman Empire, and ambitious plans were laid to resettle the country. Two hundred thousand hectares of land on arable coastal strip were confiscated and made available to some 90,000 Italian settlers who would, the plans envisaged, make up 10% of the population by 1938.

There was Libyan resistance to all this led by Omar Mukhtar, a Bedouin leader from the east of Libya, who fought a guerrilla war from desert oasis bases (and whose struggle was immortalized in the movie ‘Lion of the Desert’ starring Anthony Quinn). Italian reprisals were savage. Estimates of the number of Libyans killed

by the Italians during the occupation range from 250,000 to 300,000 and this out of a population of no more than one million. Tens of thousands were imprisoned in concentration camps where they died of hunger and disease and between 1930 and 1931 alone, the Italians executed by hanging or firing squad 12,000 in the eastern province of Cyrenaica where, coincidentally, the current rebellion has its genesis.

It was really left to Britain and to a lesser extent France to shape Libya’s postwar fate. The Americans were players as well, but later in the game. Britain’s hold on Suez and therefore Egypt was weakening as the 1940’s came to an end. Egypt had gained nominal independence from Britain in 1922 and even though Egypt’s freedom to determine her own foreign policy was secured in 1936, Britain retained control of the Suez canal and therefore the flow of oil and commerce to and from the far east.

In the post-war years Egypt struck an even more assertive pose over Suez and growing but frustrated demands that it be returned entirely to Egyptian control helped fuel Nasser’s army officer-led revolution and overthrow of the monarchy in 1952. So having bases and influence in Libya, within striking distance of Suez at a time when Soviet influence in Nasser’s Egypt was on the rise was imperative to Britain.

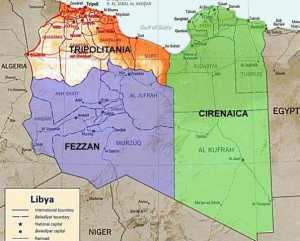

France had its North and Central African colonies to worry about: Algeria, which shares a south-western border with Libya; Tunisia, to Libya’s immediate west and Chad and Niger (the latter subsequently found to be a rich source of uranium), both with borders in the deep south of Libya. France sought influence and a presence in the deep south of Libya, in the province known as Fezzan in large part to stem any possibility of rebellion or foreign challenge to her control of, or influence over these colonies or soon-to-be former colonies.

The immediate post-war years were the age of ‘The Big Four’ in global diplomacy. The Soviet Union, the United States, Britain and France each demanded a say in the shaping of the new world although in practice it was usually the Soviets versus the rest, as the Cold War imposed the new reality. Post-Nazi Germany had been carved up into zones of influence, one for each of the victorious allies, and the same approach was tried in Libya, the former colony of another Axis power, but with less success.

The Western allies were determined to deny the Soviet Union a foothold in North Africa and this sometimes led to comical about-turns. All the powers agreed that at some point Libya would have to be given independence; what was at issue is who would have the ear of Libya’s rulers when that day dawned.

At first the Americans, eager to gain friends and influence in post war Italy, suggested that Libya be returned to her former imperial master for a decade under United Nations trusteeship, after which she would be granted independence. But when the Italian Communist Party began to grow in strength and popularity and the Soviets, seeing a perfect chance to gain influence in Libya through a proxy, seconded that proposal the Americans quickly went into reverse gear.

After the Korean War erupted in 1950, the Pentagon began to realise that Libya had strategic value. As First put it: “United States military planners resolved that the bases in Libya were not only useful but indispensable….(and) would keep the Soviet Union out of the Mediterranean”. In the immediate post-war years the US had spent $100 million dollars on the airbase at Wheelus near Tripoli but then decided to run it down. When the Korean War began she again reversed gear and poured more money and men into the base, then America’s first airbase in Africa.

But what to do with Libya? The nearest Libya had to a monarch was Muhammed Idris bin Muhammad al-Mahdi as-Senussi, better known as King Idris, although his influence really did not extend much beyond his capital in Benghazi. He was also the head of an Islamic religious sect known as the Sanusi. Both the British and the Italians recognized him as the Emir of Cyrenaica in 1920 and later as the Emir of Tripolitania but when the Italians launched a military offensive in 1922 he fled Libya and sought refuge in Egypt as Omar Mukhtar’s guerrilla war intensified. When the Second World War came to North Africa, Idris made an alliance with the British against the Axis and after Germany’s defeat their partnership survived and prospered as Idris sought London’s favors and protection, giving the British in return the greatest influence over Libya’s putative new ruler of all the Western allies.

In the context of contemporary events it is important to note that Idris was essentially the leader of a sect and tribe which had its base in Cyrenaica with its capital in Benghazi. His ties to the western part of Libya were weak. Even when Libya was made independent and Idris elevated to the throne he chose to live in a palace in Tobruk, close to the border with Egypt and almost as far away from Tripoli as it was possible to get. Over the years resistance to Gaddafi’s hold on Libya has often been financed or led by members or supporters of the Idris clan, the rebellion against Gaddafi that began last February had its genesis in Idris’

capital, Benghazi and the rebels have chosen as their flag, the standard of Idris’ Libya. They have also made alliance with the same Western powers who put and kept Idris on the throne. Coincidence perhaps, but interesting nonetheless.

It was the British in close alliance with the French who decided that independence for Libya was the best way to keep “the Russian camel’s nose out of the Libyan tent”, as Ruth First put it. To do that Libya’s future was handed nominally to the United Nations to decide and in 1949 a resolution was passed at the General Assembly granting independence which would come into effect as early as possible in 1952.

It was not anti-imperial fervor or concern that the Libyan people should enjoy the fruits of national self-determination which persuaded the United States to back Britain and France in this project but cold, hard self-interest in the ideological and political-cum-military war against the Soviet Union.

The State Department official in charge of the Libyan desk, and America’s first ambassador in Tripoli, Henry Serrano Villard, writing post facto, set out the rationale, quoted at length in First’s book:

It may be worth noting that if Libya has passed under any form of United Nations trusteeship, it would have been impossible for the Territory to play a part in the defence arrangements of the free world. Under the UN trusteeship system the administrator of a trust territory cannot establish military bases; only in the case of a strategic trusteeship as in the former Japanese islands of the Pacific are fortifications allowed; and a ‘strategic trusteeship’ is subject to veto in the Security Council.

(But) as an independent entity Libya could freely enter into treaties and arrangements with the Western powers looking towards the defence of the Mediterranean and North Africa. This is exactly what the Soviet Union feared and what Libya did. The strategic sector of African seacoast which had proved so important in the mechanized war of the desert was coming into its own as a place of equal importance in the air age.

So the British with American support chose the route to Libyan independence via the United Nations. The French, worried about Algeria and her other colonies, put up some resistance and preferred a plan to give the three provinces, Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan independence at some unstated date far off in the future. First wrote: “(France) was still fearful of the chain reaction in North Africa to the establishment of a new independent state….” But the British and Americans got their way.

To the untutored eye it looked as if the victorious Western powers had, as those who had fought a war to defeat fascist tyranny were expected to do, agreed to bestow a generous measure of self-determination, a democratic form of government and even a constitutional monarchy based on the British model to this most sadly abused Arab state. But that was for public consumption and anti-Soviet propaganda. The reality was that Libyan independence was to be a sham and Idris would be a puppet of the British and, through them, the Americans.

The game was given away, much to the horror of the newly appointed UN Commissioner in Libya, Adrian Pelt, when it was discovered that the British had negotiated the terms of a defence treaty with Idris long before independence was a reality, a treaty that was technically illegal and likely to scandalize world opinion and hobble Idris’ government before it took office should it become public knowledge.

So Pelt secured the agreement of the British that they should defer formal agreement of the treaty and even pretend to start negotiations only after independence arrived, although a separate deal with Idris that was confined to Cyrenaica was already in place and served as a model for the wider treaty.

As Ruth First wrote: “Anglo-American policy saw Libya as less a country or state than a strategic position for a series of military bases.” Britain got unlimited, exclusive and uninterrupted use of Libyan territory for military aircraft, was allowed to base its Tenth Armoured Division in the country, had an air base south of Tobruk and an RAF detachment was stationed at Idris airport in Tripoli to facilitate the strategic air corridor to East Africa, the Indian Ocean and the Far East.

The agreement was to last, initially, for twenty years and could be renegotiated when it expired. In return Britain made a contribution to Idris’ budget. This was the crux of the arrangement. In the 1940’s and early 1950’s Libya was one of the poorest nations on earth, eighty per cent of its population were nomads and its largest industry was the recycling of scrap metal from tanks and artillery pieces abandoned by the Axis and allies in the desert during the Second World War. As the Chinese would say the deal between Idris and the British was “an unequal treaty”, a document the King had little choice but to sign.

The Americans negotiated a similar arrangement for the use of the former Italian airbase at Wheelus outside Tripoli. Wheelus was integrated into Strategic Air Command and John Foster Dulles, Eisenhower’s fiercely anti-Communist

Secretary of State personally inspected the new acquisition which became a primary training base for NATO forces as well as providing American B-52 nuclear bombers access to southern Russia via Turkey and to key parts of Africa. In 1956 Wheelus became the headquarters of the Seventeenth Air Force.

Western interest in Libya was born out of a strategic necessity to confront the Soviet Union in the Mediterranean and the Middle East. With the development of intercontinental ballistic missile capacity, Libya’s value as a base for bombers diminished with the passage of time but in 1955 oil was discovered and quickly replaced defence as the focus of Western interests in this part of North Africa.

Nonetheless, Britain, America, France and in a minor way Italy all had reason to regard Libya as a legitimate battleground in the historic conflict, ‘the great game’ against the Soviet Union and international Communism. But as the Western powers staked out their ground in Benghazi, Tripoli and Fezzan, the rest of the Arab world was throwing off the shackles of colonialism or embracing pan-nationalism in the struggle against Israel and her American ally and by so doing helped write King Idris’ death sentence.

As Ruth First noted: “The price (of Libyan independence) was a state heavily committed to the West. This was to be the fundamental cause of the coup d’etat which overturned the monarchy” in 1969, a coup led by Muammar Gaddafi and his fellow “free” officers in the Libyan army. It is surely no accident that the same foreign forces, America, Britain, France and Italy have returned to extract their payback.

You must be logged in to post a comment.