Who Were the Volunteers? The Shifting Sociological and Operational Profile of 1240 Provisional Irish Republican Army Members

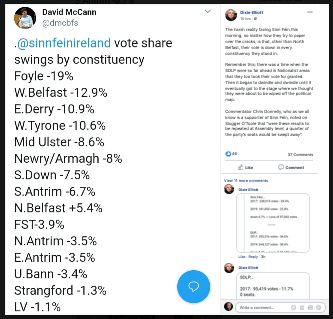

By Paul Gill & John Horgan

PAUL GILL – Department of Security and Crime Science, University College London, London, UK

JOHN HORGAN – International Center for the Study of Terrorism, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, Pennsylvania, USA

This article presents an empirical analysis of a unique dataset of 1240 former

members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA). We highlight the shifting sociological and operational profile of PIRA’s cadre, and highlight these dynamics in conjunction with primary PIRA documents and secondary interview sources. (Tables are listed at the end of the article)

The effect of these changes in terms of the scale and intensity of PIRA violence is also considered. Although this is primarily a study of a disbanded violent organization, it contains broad policy implications beyond the contemporary violence of dissident movements in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

We conclude with a consideration of how a shifting sociological profile impacts upon group effectiveness, resilience, homogeneity, and the turn toward peaceful means of contention.

Introduction

John Whyte famously wrote that Northern Ireland ‘‘is the most heavily researched area on earth.’’2 It may be surprising that yet more research on Northern Ireland, especially on the Irish Republican Army, could possibly offer a substantial contribution to the heaving literature that already exists on ‘‘The Troubles.’’

The worrying rise in contemporary dissident terrorist activity in Northern Ireland provides the context for many of the recent examinations of those particular groups.3 Yet curiously absent from much of the astonishing array of literature on Irish Republicanism are empirical, data-driven perspectives of those who engaged in non-state paramilitary activity throughout the Troubles.

There are notable exceptions4 of course, but by and large empirical analyses of political violence in Northern Ireland at the individual level have been scarce, a point reflected in the broader terrorism studies and civil war literature, at least until recently.

Fortunately, however, in recent times many individual-level analyses that

were characterized by a preoccupation with such notions as ‘‘predispositions’’ for

involvement have given way to more promising avenues for examining the activity of those individuals who became involved in terrorism.

These include studies on al-Qaeda, Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA), foreign fighters in Iraq, and Colombian, Pakistani, Palestinian, and South-East Asian militants.5 Collectively, such approaches provide an empirical basis for hypothesis testing about those who join terrorist movements such as when, where, and how they became involved, the activities they took part in, how they fit into a wider networked structure, and how they ultimately disengaged.

In this article, we hope to contribute towards this development by offering an

account of the shifting sociological and operational profile of Provisional Irish

Republican Army (PIRA) members between 1970 and 1998. The analysis presented here is drawn from a new dataset of 1240 PIRA members, developed as part of a larger research effort on malevolent creativity and innovation in terrorist networks. The database includes thirty-nine variables across temporal, socio-demographic, and operational domains.

The relatively large time frame (almost 30 years) under consideration allows us to use a time-series analysis to examine variations across age, location, roles, employment status, and other variables. We can place such changes against the shifting organizational structure and the dominant strategic and tactical logic of the PIRA over time.

Changes in environmental conditions such as the changing nature of Britain’s

counter-terrorism policy also impact upon these changes within PIRA. Using the data as a starting point, our analysis is complemented by additional insights from seminal studies on PIRA history, primary source PIRA documents, and secondary interview data to help explain these shifts.

With the exception of Reinares’ research on ETA,6 efforts to engage in such endeavors through triangulated methods remain relatively unexplored.

A Brief History of the IRA

PIRA was formed in December 1969 as a breakaway movement from the older,

original Irish Republican Army. The 1969 split gave rise to both PIRA and a group calling itself the Official IRA (OIRA).

One 7 catalyst for the split was an internal disagreement among Irish Republican militants about the appropriate response (e.g., violent vs. non-violent) to widespread resistance and intimidation against Catholics in Northern Ireland, set against a backdrop of a developing Civil Rights movement within Northern Ireland seeking social and economic parity for Catholics with their Protestant neighbors.

OIRA on the other hand are largely depicted as rivals having a Dublin-based and Marxist-inspired leadership who were more interested in taking a laissez-faire approach—aiming instead to unify Catholic and Protestant working classes.

While not entirely without its merits, this depiction overlooks the fact that OIRA engaged in a military campaign untilMay 1972 and actively recruited personnel in competition with PIRA. PIRA framed themselves as defenders of the Catholic communities under threat by sectarian Loyalist mobs (often passively or

actively supported by the local police force—the Royal Ulster Constabulary) who

had attacked Civil Rights marchers, Catholic-owned businesses, and Catholic housing estates that drove thousands from their homes.

While these dynamics and others have been captured in seminal historical accounts8 and firsthand accounts by disengaged militants,9 there remain few adequate accounts of who joined PIRA that go beyond personal recollections and largely anecdotal description.10

To provide an account of the recruitment patterns and operational profiles

amongst PIRA members, this article disaggregates PIRA’s campaign into five discrete phases of activity. The first phase covers 1969–1976.

Over the course of this period, PIRA structured themselves like an Army with various brigades, battalions, and companies. Each unit was responsible for specific geographical combat areas. Indiscriminate violence by all sides of the conflict marked this period, the most defining moment of which was ‘‘Bloody Sunday’’ when the British Army shot and killed thirteen innocent

civil rights marchers.

This was an unprecedented propaganda coup for PIRA and led to mass recruitment and mobilization. Civilian fatalities attributed to PIRA also peaked

during this phase and included the events of ‘‘Bloody Friday’’ where, in the space of under two hours, 22 improvised explosive devices (IEDs) killed 9 (6 civilians, 2 British Soldiers, and 1 member of the Ulster Defence Association) and injured a further 130.

1977–1980 covers the second phase and is significant for a number of reasons.

First, there was a large-scale re-organization of PIRA’s structure to a tighter,

cellular-based network in which cells acted independently of one another. This

change placed far less emphasis on the quantity of Volunteers and far more emphasis on secrecy and discipline.

Almost instantly, the effects of the structural changes were

noticeable.

465 fewer charges for paramilitary offences occurred within a year.11

Second, a number of leadership changes occurred whereby younger Northern born and bred members such as Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness who respectively became PIRA Chiefs of Staff in 1977 and 1979 took charge.12 This largely came about through the creation of a Northern Command that coordinated operations across the six counties of Northern Ireland.

1981–1989 encompasses the third phase and covers the growing politicization of

the Republican movement which occurred after the Hunger Strikes. In total, ten

Republicans died on hunger strike in 1981; seven were PIRA members. PIRA’s

Bobby Sands had been elected to Westminster after winning a by-election while

on hunger strike.

Sympathy for PIRA began to rise again and this was largely channeled toward PIRA’s political wing, Sinn Fein, by organizational elites such as McGuinness, Adams, and Republican strategist and publicist Danny Morrison.

Phase four (1990–1994) covers the negotiations and pathway toward ceasefires

undertaken secretly by organizational elites. Much of this was carried out unbeknownst to the wider cadre.

Phase five (1995–1998) covers the period in which the negotiations

were made public and the march toward the final ceasefire and the Good

Friday Agreement that symbolized for many the end of the Northern Ireland conflict.

The PIRA Militant Database

The database contains information on 1240 individuals who were either convicted of PIRA-related activities (including membership) or died on ‘‘active service,’’ a term used by PIRA to describe members’ involvement in PIRA-related activities.

Who Were the Volunteers? 437

For the purposes of this article, being engaged in ‘‘active service’’ includes both violent activities (e.g., bombing attacks), and non-violent activities (e.g., training accidents).

The individuals were identified from a number of open-sources: a) statements by the Irish Republican Army including their annual Roll of Honor which commemorates their war dead; b) the Belfast Graves publication that offers an account of Republicans killed in combat;13 c) McKittrick et al.’s Lost Lives which provides an obituary of each civilian and (para-)military victim of the Northern Ireland conflict;14 d) historical accounts of PIRA from academic sources; and e) newspaper archives.

Once a substantial number of names (300þ) had been identified from these sources, a team of fourteen coders used the Irish Times newspaper archives to complete the data fields. Each entry of a PIRA member was coded twice to ensure inter-coder reliability. As each individual was coded, the names of other PIRA members within the article were added to our actor dictionary, allowing for future social network analyses.

Upon completion, this information was augmented by information in the above sources. For each individual the database captures 39 data points. The

information captured includes name, a unique identifier number that anonymizes the individual so that the database can eventually be made public to other researchers, alias, gender, highest level of education achieved, organizational affiliation, sub-unit affiliation, year of birth, age at earliest identifiable paramilitary activity, the phase of the conflict in which they took part in their first activity, the year of first identifiable activity, whether they were killed in combat (and if so, their age of death, the year of death, and the phase of the conflict in which they died), their place of birth (whether it was North or South of the border, the province, the county, town=village size, urban=

rural), their known address at the time of the activity they were convicted of (whether it was North or South of the border, the province, the county, town=village size, urban=rural), marital status, whether they had children (and how many), occupation, occupation type, positions held within the organization (when they held them and at what age), years active, arrests,15 prison terms, and attacks linked to.

While the data are sufficiently large, reliable, and dense for the analysis that

follows, some caveats are appropriate. It is not a complete dataset of all PIRA members.

Such an undertaking would result in a much larger dataset that due to time and

financial constraints would be very difficult to complete. Further, many PIRA members may have eluded convictions and hence escaped our data collection protocols.

The observations are also non-random due to the original sources used to build the actor dictionary. There is no way therefore to estimate the effects that missing observations have upon the analysis that follows but we feel that the sample size is sufficiently large enough that we can be relatively confident about the robustness of our findings.

Finally, The Irish Times archive is the sole newspaper source used for the

database. For practical (needing access to digitalized newspapers) and financial

reasons, we could not add other newspapers such as The Belfast Telegraph into

our data collection capabilities. Such a source may have added data density to

variables that proved troublesome to consistently collect data on.

Age of First PIRA-Related Activity and Recruitment Policy

The PIRA militant database catalogues the age at which we can confidently identify the individual’s first act of paramilitary activity. This is not identical to identifying exactly when the individual joined the group. Given the secretive nature of involvement in terrorist activity, as well as the challenge of disaggregating involvement from actual engagement in activity (often synonymous in a legal sense, where membership constitutes an illegal act)—the specific age of recruitment is unattainable in most cases.

For the vast majority of the individuals in our database, this field encapsulates the age at which they committed their first PIRA-related activity that led to a conviction. The outliers to this trend encapsulate those Volunteers who died in action. In these cases,

PIRA’s Publicity Department, through their newspaper An Phoblacht, often released fine-grained information on when and why the individual joined the group. While some sources may state that an individual joined the ‘‘Republican movement’’ at a certain age, such a source fails to reach our standards of both a) what constitutes PIRA-related activity and b) what constitutes activity that may lead to a conviction.

In sum, age of first identifiable PIRA activity is the best that can be captured in this type of data collection effort short of a major undertaking of primary interviews.

The average age at the time of first identifiable PIRA-related activity that we can

accurately account for is 24.99 years old. On average, female recruits were a year and a half older than their male counterparts at the time of first PIRA-related activity (26.56 vs. 24.91).

The total average age is very similar to Sageman’s16 findings on global jihadists who averaged 25.7. The average age however is markedly older than

Florez-Morris’ sample of Colombian militants who averaged 20 years.17 It is also

much younger than the average age of 35 identified by Horgan and Gill in their sample of dissident Republicans active in Northern Ireland between 1999 and 2010.18

Given the length of time under consideration here, it is perhaps not appropriate

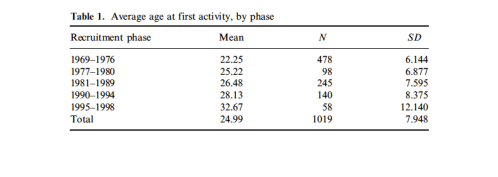

to make these like for like comparisons as the average age is likely to fluctuate across time because of organizational recruitment policy, tactics, strategies, and the contemporary dynamics of the campaign itself. Calculating the average age by phase shows an interesting pattern in that the average age of new recruits gets older as the campaign of violence progressed (see Table 1).

Phase one recruits averaged 22.25, displaying a far closer average to Florez-Morris’ sample mentioned above.19 Phases two and three averaged 25.22 and 26.48 respectively. Phase four averaged 28.13 and phase five averaged 32.67 (see Table 1). These figures are consistently higher than the average of

those IRA volunteers who died on ‘‘active service’’ (phase one: 21.25, phase two: 24.3, phase three: 21.23, phase four: 22.77, and phase five: 18.5).

Taking into account Horgan and Gill’s findings on those active post-Good Friday Agreement, we can see a long historical trajectory of new recruits becoming older and older the longer the conflict ensued.20 Interestingly, the inverse was found to be true in Reinares’ sample of ETA militants.

Despite ETA and PIRA’s striking similarities in structure and the nature and length of their conflict, the temporal dynamics of who joined these militant groupings were totally opposite as their campaigns of violence progressed.

Table 1. Average age at first activity, by phase

It is a well-established fact that the longer ‘‘The Troubles’’ ensued, the fewer

fatalities PIRA caused.21 Over the course of phase one PIRA caused an average

of 104 deaths each year. This figure dropped phase by phase from 66 in phase

two, to 53 in phase three, to 37 in phase four and 6 in phase five.

While organizational level (e.g., top-down) analyses stress that the growing politicization of the PIRA movement caused this decrease in fatalities, our analysis offers another compatible dimension.

From an individual level (e.g., bottom-up) perspective, the older PIRA recruits became the less likely they were to engage in violent activities that led to fatalities. This makes sense when we consider that a rich body of work from the criminology literature illustrates that younger people typically engage in more violent and illicit activities than older individuals. Alternatively, the increasing ageprofile of new recruits may also reflect organizational-level concerns and requirements.

It is also important to note that these average ages are aggregate sums of

the cadre as a whole and will include leaders and foot soldiers. While leaders typically tended to be older than the foot soldiers, our analysis shows that the difference in age between senior figures and new recruits lessened significantly as the conflict progressed.

While leaders are clearly important, they do not directly take part in violent

activities. Instead, their orders diffuse down a chain of command. While younger

people more readily engage in violent activities, the lack of new young recruits (either through deliberate recruitment policies or through indifference amongst newer generations toward the Republican movement) certainly constrains the scale and intensityof potential violent campaigns.

This finding contains immediate relevance for not only risk assessments of terrorist groups at an aggregate level but also for measuring the likelihood of a group moving toward collective disengagement.

Importantly, close to two-thirds (64.7%) of the sample were between the ages of

10 and 22 when Bloody Sunday occurred. Just under a quarter (23.8%) of the sample were at this vulnerable age during the 1981 Hunger Strikes. These two events are seen by many as the two seminal watershed moments in the Northern Ireland conflict that increased passive and active support for PIRA activities.

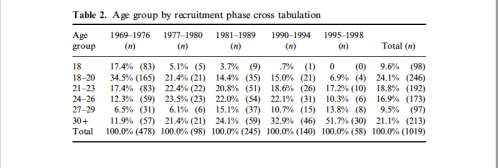

Indeed, Table 2 illustrates that a third of PIRA recruits’ first identifiable activity occurred before their 21st birthday. Although youth is not necessarily a causative factor in why people join terrorist movements, there is a high correlation between it and engagement in high-risk activities and is well established as a strong risk factor for involvement in direct terrorist activity.22

The finding that the perpetrators of violent crime are more likely to be males between 15 and 25 is a statistically robust finding that remains constant cross-culturally.23 Silke argues that the same factors that allure young males into illicit activity, including political violence, may include ‘‘higher impulsivity, higher confidence, greater attraction to risk taking and a need for status.’’

Silke also points toward research that indicates that young men more often

hold positive attitudes concerning revenge. This may be partially reflected in

Table 3 which illustrates the salient effect proximity to the conflict has upon the

age of first identifiable activity and thereby recruitment. The closer in proximity

to the main conflict area (which mainly occurred in the six counties of Northern

Ireland), the younger the new recruit tended to be.

This remained fairly consistent through the five phases under study with two exceptions. Phase 2 recruits from the North and South share near identical averages. English-based operatives are almost three years younger than those operating in Northern Ireland.

However, far more young men, who experienced the same socialization in

Northern Ireland, did not join PIRA than those who did. Other factors would therefore appear concurrently relevant in why people join politically violent movements.

Most studies on why people join terrorist movements mostly focus upon the

‘‘supply-side’’ of the process and fail to account for the ‘‘demand-side.’’ By focusing upon the underlying conditions and presumed individual dispositions that create a large pool of potential recruits, these analyses ignore impediments to membership.

Explaining the process through which organizations recruit is essential. Social movement theorists have long focused upon this issue.25 In essence, social movement theorists posit structural availability as being more important than attitudinal affinity to a cause. A desire to become a PIRA member, therefore, is of little use if the would-be member does not possess the structural opportunities to join.

Quite often, pre-existing social and=or familial bonds overcome this constraint and facilitate the recruitment process. Oftentimes, the contemporary recruitment policy or organizational structure can also act as a structural constraint. For example, the large shift from younger to older recruits is vividly outlined in Table 2.

Whereas between 1969–1976, 17.4% of new recruits could be classified as minors, this type of recruit gradually became scarcer before becoming seemingly extinct between 1995 and 1998. The percentage of those 18–20 also drastically fell 27.6% across the period under examination. One factor that may account for this is the changing relationship between PIRA and its youth wing, Na Fianna Eireann.

In the early years of the conflict, PIRA leaned upon Na Fianna Eireann for early socialization and recruitment: The purpose of the youth organization . . . was to prepare young men to progress into the ranks of the IRA at a later stage, so there would have been a certain amount of education . . . although it wasn’t anything

comprehensive or it wasn’t very sophisticated. It would have focused very

heavily on the republican tradition within Irish history. . . . [It was] quite often a source of scouts for the IRA, they would watch the area for local volunteers, they would inform volunteers if the Brits were in the area, they would ensure that the area was safe for local volunteers to move about either individually or with weaponry and they would play a very peripheral role in some IRA operations.26

Former Na Fianna Eireann and PIRA member Robert McClenaghan elaborates

further: We were the junior so we would have been out in front looking to see if

there was any British army, looking to see if there was any RUC. The older volunteers in the IRA—they would have come out and done the shooting or whatever it was they were involved in. They would have given the weapons to us and then we would have took the weapons away and put them into a safe place.27

The recollections of another former PIRA member, Brendan Hughes, concerning

PIRA’s recruitment policies in the 1970s, largely confirms our empirical findings.

Following the feud between PIRA and OIRA that largely culminated in March 1971 after a period of intra-communal violence, he asserts that, ‘There was a major influx of youngsters coming in . . . you had the Fianna at this time, young kids, from twelve to sixteen, [but] they had to be over fifteen to be trained in weapons, both Fianna and the Cumann na gCailini [girl’s version]. They were potential recruits [to the adult IRA]; they did scouting work, for instance . . . on their way to school’.28

As Table 2 suggests, there was a large shift in recruitment patterns toward older

individuals. A key reason for this is the shift in organizational structure outlined

briefly above. The blueprint to this organizational shift was seized in December

1977 when Seamus Twomey, a leading figure in PIRA, was arrested. The documented, entitled ‘‘Staff Report,’’ outlined the following: ‘We are burdened with an inefficient infrastructure of commands, brigades, battalions and companies. This old system . . . has to be changed. We recommend reorganization and remotivation, the building of a new Irish Republican Army. . . We must gear ourselves towards Long Term Armed Struggle based on putting unknown men and new recruits into a new structure. This new structure shall be a cell system. . . . Na Fianna Eireann should return to being an underground organization with little or no public image. They should be educated and organized decisively to pass into IRA cell structure when of age’.29

In other words, one key component of PIRA’s restructuring in 1977 was to minimize the public face and position of a resource that had provided an abundance of new young recruits for the previous decade. By going underground, it ensured fewer recruits and therefore a smaller band of new recruits who were minors. This is reflected in the drop from 17.4% to 5.1% between phases one and two.

As the Republican campaign became more politicized through the workings of Sinn Fein, Na Fianna Eireann was totally disbanded during the 1990s and replaced with a youth party for Sinn Fein (Ogra Sinn Fein). The emergence of Ogra Sinn Fein is largely reflected in PIRA’s recruitment policies (or lack thereof) of minors from 1990 onwards.

Table 2 also illustrates that recruits older than 30 consistently encompassed a

significant number of new recruits, but this reliance became greater across time, culminating in the final phase where over half of newly identified recruits fell into this age category. It is the shift away from recruiting those under 20 to recruiting those over 30 that accounts for much of the increased average age illustrated in Table 1.

Gender

There is a long, storied tradition of females active in Irish Republican militancy dating back to the 1916 rising in Dublin against British rule and the role played by Cumann na mBan—a female auxiliary paramilitary force dating back to 1914.

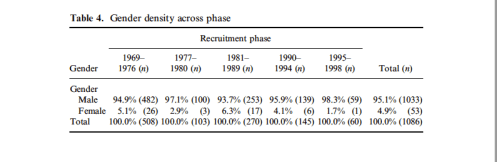

Our data suggests that female PIRA recruits remained a minority throughout the Northern Ireland conflict (see Table 4). Across the course of the conflict, women account for approximately one in twenty militants in our database. This could be for a number of reasons. First, as mentioned above, males are typically more attracted to high-risk behavior and revenge than females. Second, recruiters typically targeted males. Third, the typical roles and behaviors that women engaged in within PIRA tended to be behind-the-scenes support work such as providing cover to male PIRA volunteers, providing safe houses, acting as couriers (of weapons, explosives, money, and sometimes just simple information through paper messages), and acting as look-outs for male operatives.30

For Moloney, Cumann na mBan through the early 1970s acted as the ‘‘IRA equivalent of being stuck in the kitchen and the bedroom; they carried messages and smuggled weapons and explosives and they nursed wounded IRA volunteers. They could be useful for gathering intelligence and carrying weapons, but they did very little, if any, actual fighting.’’31

This form of behavior is unlikely to lead to anywhere near as many convictions (and hence emerge in our data collection efforts) than other front-line violent activities such as planting or constructing IEDs.32 A repeated theme throughout firsthand accounts by male PIRA militants is that they rarely knew the identities of the females who helped them on their missions.33 This is not to suggest however, that there were no prominentfemales engaged in violent activities.34 Famous examples include sisters Marian (Table 4. Gender density across phase)

and Delours Price who took part in co-ordinated bombings in London in 1973;

Mairead Farrell who was captured in 1976 planting bombs in Dunmurry and later killed in Gibraltar by the SAS while on another bombing mission in 1988; Martina Anderson who was convicted in June 1986 of conspiring to cause explosions in England and is currently a Member of the Northern Ireland Assembly; Pauline Drumm, Pauline O’Kane, and Donna Maguire who were all convicted in German courts of attempting to murder British soldiers; and Ella O’Dwyer who was convicted of conspiracy to commit bombings across England in 1985.

In essence many of the most famous female recruits were foreign operatives. In fact, female recruits also represented a disproportionate number of activities in mainland England.

12.7% of the operatives that took part in activities in England were female. Not

all of these operatives took part in high-risk behaviors however. Through the late

1970s and 1980s, Cumann na mBan provided at least ten trained couriers who would pass messages between PIRA elites to the ground-level cell leaders.35

The concentration of women did fluctuate across time however, peaking in the

phase that followed the Hunger Strikes (in which three female militants also took part).36 During phase one, under Gerry Adams’ leadership, the Belfast Brigade began recruiting women absent of Cumann na mBan membership.37

This helps account for the relatively high numbers of women in this phase, especially when we consider phase one as being the most represented phase in our total database. As a response, the alienated Cumann na mBan’s leadership refused to take orders from PIRA for a period of time.38

PIRA’s structural changes account for phase two’s subsequent drop in

numbers. The ‘‘Staff Report’’ alluded to above also mentions the following:

Cumann na mBan [PIRA’s female unit], we propose, should be dissolved

with the best being incorporated in IRA cells structure and the rest going

into Civil and Military administration.39

PIRA’s restructuring in 1977 therefore reduced the front-line role and need for

female recruits and our findings empirically demonstrate this. Although the depth of female recruits spiked in phase three, this was immediately followed by two periods of decline.

Birth and Operational Location

Two political entities govern the island of Ireland. The Republic of Ireland encompasses the twenty-six Southern counties. Northern Ireland (as part of the ‘‘United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland’’) covers the six Northern counties of Derry, Antrim, Armagh, Down, Tyrone, and Fermanagh.

The island is also split into four provinces: Connacht in the West, Leinster in the East, Munster in the South, and Ulster in the North. Ulster and Northern Ireland are not coterminous. The six counties of Northern Ireland all belong to Ulster but so too do three other counties that are part of the Republic (Donegal, Monaghan, and Cavan).

We have collected data on the birth location of 503 militants (see Table 5). Given

92.8% of the total deaths attributed to the conflict as a whole occurred in the six

counties of Northern Ireland,40 it is unsurprising that the vast majority (82.7%) of our sample were born there. 13.9% of the sample were born in the Republic of

Ireland while a much smaller number were born in England and the United States.

Our data are denser when we account for the location the individual inhabited at

the moment we can pinpoint their first PIRA-related activity. This is because current address is regularly mentioned within newspaper accounts of court proceedings.

Table 6 illustrates that figures for Northern Ireland are 10.5% lower than the birth location figures while those living in the Republic rise to 21.5% and those living in England double their proportion.

The question remains however, where in the Republic of Ireland exactly did

these individuals migrate toward? Once we categorize the leap in provincial terms,

the shift from North to South is not so dramatic as the three border counties of

Donegal, Monaghan, and Cavan are characterized as being in Ulster. Horgan and

Taylor also note that PIRA’s Northern Command further included counties Leitrim and Louth.41 (See Table 5)

When these two counties are added, the operational figure for PIRA’s

Northern Command rises to 86.8%. In effect, operational members of Northern

Command, upon leaving the Northern six counties, tended to migrate towards other counties under the auspices of Northern Command.

Typically, those within Southern Command provided logistical support for

Northern command. Prime activities included training, funding, storage, and movement of weaponry and explosives and provision of safehouses.42 A surprisingly small number of PIRA cadre come from the Southern province of Munster. This is particularly surprising considering that PIRA possessed approximately 230 safehouses across the province and that much of the training took part there.43

Again, these types of activities may be more elusive to the security community and perhaps undercounts the true number in this area.

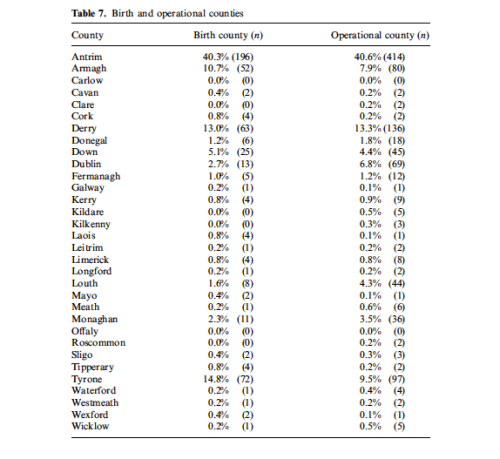

Antrim, mainly because of the capital Belfast, is the most represented county in

terms of where the individuals were born (40.3%) and where they were located at the moment of first PIRA related activity (40.6%). Again, this is not surprising considering the vast majority of both IED events and deaths occurred here throughout the period of the conflict.

Tyrone is the county with the second highest birth location of our database with (14.8%), then Derry (13%), Armagh (10.7%), Down (5.1%), Dublin (2.7%), and Monaghan (2.3%). All of the counties apart from Carlow, Clare, Kildare, Kilkenny, Offaly, and Roscommon are represented here. Some differences

occur when we focus upon operational county. Derry is the second most represented county for individual operational location (13.3%), followed by Tyrone (9.5%), Armagh (7.9%), Dublin (6.8%), Down (4.4%), Louth (4.3%), and Monaghan (3.5%). All of the counties apart from Carlow and Offaly are represented here (see Table 7).

Table 8 illustrates the shifting nature of operational location across the five

phases under examination. There is a clear downturn in the number of operatives active within the Northern six counties the longer the conflict went on. This is largely explained by the dramatic drop in density amongst Antrim- and Belfast-based operatives from 46.7% in phase two to 27.1% in phase three. In effect, the onset of the Hunger Strikes and the growing politicization of the movement acted as a scale shift (Table 6. Location at time of conviction=active service death; Table 8. Operational location across recruitment) away on an aggregate level from operatives embedded in Belfast and Antrim toward

a much higher presence in both County Derry (8.7%), and the Republic of Ireland (8.8%). Membership rates within the Republic continued to expand as the conflict continued.

Interestingly, this process occurred as the leadership and elite level itself

became far more Antrim- and Belfast-centric and moved its base of operations and regular meetings away from Dublin.44 This also occurred at a time when operational leaders such as Brendan Hughes noticed a downgrading in the capabilities of Northern IRA Brigades and cells to successfully fight against the British.45

The higher activity within the Republic of Ireland during the phases of negotiations with the British (both secret and open) may also reflect a growing dissension amongst the Southern cadre in the peace process. This dynamic continues with contemporary dissident groupings whose older members generally tend to be from the Republic also.46

This assertion is further strengthened when we see that places like Dublin, Armagh, Louth, and Tyrone,47 four hubs of contemporary dissident recruitment, witnessed the largest spikes in overall density between phase one and phase five.

In effect, much of the internal factions within PIRA through the 1970s concerned having a largely Southern-based leadership who alienated the majority Northern-based cadre. From the onset of the politicization of the Republican movement, we see a largely Belfast-based leadership leading to the alienation of Southern-, Tyrone-, and Armagh-based cadre.

Town Size

Census records are freely available from both the Central Statistics Office in the

Republic of Ireland and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. City, town, and village populations for 1971, 1981, 1986, 1991, and 1996 are available for the Republic of Ireland. The same statistics are available for 1971, 1981, and 1991 for Northern Ireland. This allows for an analysis of the town sizes PIRA members typically operated in.

For those individuals we could confidently assert a known address at time of first identifiable PIRA-related activity, we used the closest census record. For example, if a member was born in Belfast in 1978, the 1981 census records were

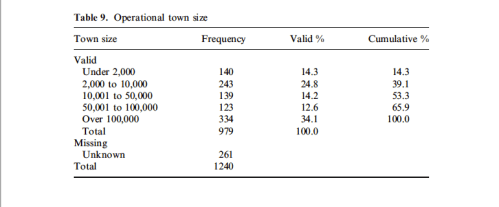

used to calculate town size. Table 9 provides a breakdown of the aggregated results.

Just over one third of our sample of 979 militants operated in a city with a

(Table 9. Operational town size) population of between 2,000 and 10,000. The findings serve as further empirical demonstration that PIRA was largely an urban-based organization.48

It also largely reflects research on the geography of guerrilla warfare, which demonstrates that contemporary guerrilla fighters are more likely to operate in urban areas because of the comparative advantages that occur with high population densities.49

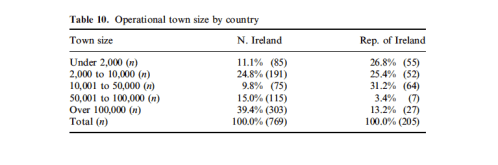

There is an inverse relationship between town size and operational location

depending upon whether the recruit operated in Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland. Recruits based in the Republic of Ireland are much more likely to be based in smaller villages and towns and much less likely to be based in bigger towns and cities than their Northern colleagues. Much of this can be accounted for by Belfast, which is the only city in Northern Ireland with a population greater than 100,000 during the time period under consideration here. See Table 10.

The town sizes operatives were based in also changed a number of times across

the phases of the Northern Ireland conflict. First, following PIRA’s reorganization, there is a spike in the number of recruits based in villages and small towns with populations under 2,000. This phase saw the proportion of recruits in these areas increase by 250%.

As mentioned previously, PIRA’s re-structuring led to 465 fewer charges for paramilitary offences occurring within a year.50 The re-structuring however

did not occur nationwide. Instead, the Staff Report, which suggested these

changes, only applied to command areas based in towns and cities. ‘‘Rural areas,

we decided, should be treated as separate cases to that of city and town Brigade=

Command areas. For this reason our proposals will affect mainly city and town

areas, where the majority of our operations are carried out, and where the biggest proportion of our support lies anyway.’’51

This change may have been a product of an independent spirit amongst PIRA cadre in the countryside. It may also have been a reaction to the urban-based leadership of Adams (Belfast) and McGuinness (Derry).52

Regardless of the reasons why, the outcome of the re-structuring made the

capture, arrest, and conviction of urban-based (particularly those in towns with a

population of 2000–50,000) cadre less likely. It consequently increased the likelihood for those based in rural areas and hence the spike within our dataset.

In other words, this particular spike is not a product of a shifting recruitment and operational practice but rather the product of tighter, more disciplined urban units whose cadre were less likely to be convicted and hence end up in our database. The large fall in numbers from those based in cities over 100,000 people from 1981 onwards is discussed above in relation to the narrowing numbers of Belfast-based militants at the expense of those based in Derry, large Dublin towns, and elsewhere. (See Table 11.Table 10. Operational town size by country Town size N. Ireland Rep. of Ireland).

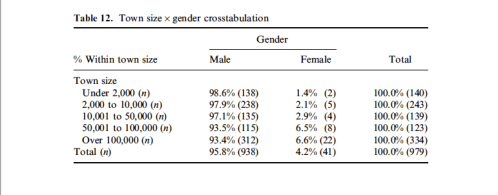

Table 12 illustrates that the larger the town size, the greater the proportion of

women operating there. When we consider the large support role most female members played within PIRA, it is no surprise to find them more readily in areas where the vast majority of combat took place; e.g., the cities of Belfast and Derry are both at the larger end of the population scale.

Marriage and Family

The database also captures marital (n¼536) and family status (n¼425) information. 41.6% were married (either at the time of recruitment or during their PIRA career) and a similar figure of 41.4% have children. There may be somewhat of a reporting bias here. The fact a recruit is married is more likely to be reported and hence picked up by our data collection efforts. This problem is shared however by similar types of studies so comparisons are valid. The figure is comparatively high compared to ETA at 11.6%,53 Pakistani militants at 14%,54 comparable with contemporary dissident Irish Republicans55 whose married cadre number just over 50% and much less than (Table 11. Operational town size by recruitment phase) Sageman’s sample of global Jihadis at 73%.56

Of the PIRA sample, those from the North were less likely to be married (37.2%) compared to their Southern (51.9%) and English-based operatives (52.6%).

There is no link between the rising recruitment age and the marriage levels across the five phases. 39.8% of phase one recruits were married compared to 35.3% of phase five recruits. The rising age of the cadre however has an expected relationship with the propensity to have children.

Whereas 35.8% of the cadre in phase one had children, this figure rose to 58.3% in phase five. The large numbers of married PIRA members is perhaps not surprising. White and White’s exemplary study On the Resources of Urban Guerrilla7 analyses the effects of marriage on career length and effectiveness of 67 deceased Belfast-based PIRA members.

The analysis shows that married members have longer career lengths (avg. of 16 months longer) and the authors argue that this is because of the greater interpersonal resources that marriage entails, which in turn provide

resources such as emotional support and provision of safe houses.

Atran’s study of contemporary militants in Indonesia came to the same conclusion.

Occupation

We have data on the occupation type of 422 of the observations in our dataset.

Members vary across a broad spectrum of occupation types. Construction accounts for over a third of this sample (35.7%). Of those in construction, 61% were in specialist positions such as electricians, engineers, plasterers, and carpenters compared to the rest, who were laborers and handymen.

Given the skills required in bomb-making, this is perhaps unsurprising and may be driven by a selection effect. Recruiters carefully choose who can join the organization and at times there could be a skill-based

recruitment drive.59

A further 27.7% worked in the services=industrial industries (specialist 11.6%, non-specialist 16.1%). Those unemployed encompass the third highest category at 11.4%. A number of our categories overlap with Reinares’ categorizations of his ETA sample.60 As well as construction, PIRA members are also far more likely to be unemployed (11.4% vs. 0.6%), and less likely to be students (2.8%

vs. 16.2%), a professional or in the services=industrial sector (34.6% vs. 59%), or in clerical, administration or sales (6.9% vs. 21%) than their ETA counterparts.

PIRA cadre active in the occupied six counties were more likely to be in the

non-specialized services=industrial sector (18.3% vs. 11.5%) and non-specialized

construction (16.7% vs. 11.5%) than their Southern-based colleagues and less likely to be professionals (3.5% vs. 9.6%), unemployed (11.3% vs. 15.4%), or involved in agriculture (3.5% vs. 8.7%). Those active in England however are evenly spread across most of the categories and far less likely to be involved in construction (25%) compared to those active on the island of Ireland.

Roles

Both the empirical and theoretical investigations of roles within terrorist movements remain overlooked. Typically studies on who joins a terrorist group tend to suffer from a categorization error. By aggregating all actors to the label ‘‘terrorist,’’ they miss many of the key differences within the sample that may come to light if some form of disaggregation in role types is deployed. The PIRA militant database captures information on the age at which the individual first took part in any number of illicit activities.

This was not possible for all of our militants as many were just convicted of either being a member of a paramilitary organization or possession of materials. The main recurring categories were gunman, bomber, criminal activities

(including hijackings, bank robberies, kidnappings, and drug dealing), bomb-maker, and gunrunner. Role types are not mutually exclusive. If for example an individual engaged in a shooting and bombing attack (at the same time or at different stages in his=her PIRA career), the individual was coded as both.

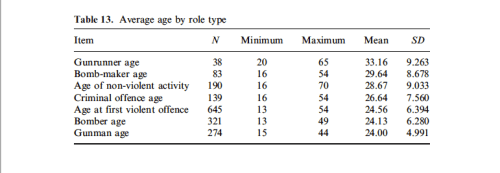

The results below suggest there is a clear disparity in the age at which individuals are likely to first engage in certain types of terrorist activity. For example, there is a four-year age gap between the average age of first conviction for a violent offence compared to the average age of first conviction for a non-violent or support role activity. This pattern holds true across all five phases of the conflict. It is perhaps not surprising therefore to find individuals convicted of shootings (24) and planting bombs (24.13) at the lower end of the average age spectrum.

Those convicted of criminal activities average a slighter higher age (26.64) while bomb-makers (29.64) and gunrunners (33.16) are typically much older than the individuals engaged in proximal violent activities such as planting IEDs and shooting incidents. Bomb-makers were consistently older than bombers across each of the five phases.

The disparity in age also got wider across time; in phase one the gap was two years whereas by phase five the gap was twelve. While the average age of first-time activity for the sample as a whole increased by ten years from phase one to phase five, the average age of bombers only rose by four years, which suggests the profile of those engaged in this type of activity changed very little across time.

The average age of bomb-makers on the other hand increased by fourteen years from phase one to five. See Table 13. The discussion above concerning youth and proclivity to engage in violence is even more important here when we consider that the older the recruit becomes, the less likely the recruit is to be engaged in front-line violent activities.

The results also suggest that the career trajectories and role migration of individual members of terrorist groups should be examined more closely. While this type of study is currently flourishing in the criminology field, it remains unexplored in relation to terrorism and political violence with one exception.61

There are other considerable differences between role types. 8.7% of those in

engaged in planting bombs were women, at least double the density of each of the other role types under consideration here. This is likely to be the case because women could transport bombs in their clothing, in prams, or as part of a couple in order to arouse less suspicion from the police and security services.

The density of bombers recruited by phase closely mirrors the scale of bombings across the five phases.

Table 13. Average age by role type

62.2% of the gunrunners’ first activities took place in phase three, directly following the Hunger Strikes, which is more than double the density for this phase than any of the other role types. This can be largely traced to the intended replication of the ‘‘Tet Offensive’’ tactics that was to take place during this time.62

Those engaged in criminal activities and gunrunning were more likely to be operational outside of the occupied six counties, particularly in the border county of Co. Louth. These individuals were also far less likely to be married and have children compared to those engaged in violent activities like bombings and shootings. In sum, these findings suggest that researchers have used the incorrect dependent variable when analyzing who joins terrorist organizations.

Instead of who becomes a terrorist, the more pertinent question may be who becomes a bomb-maker as opposed to a gunman and so on. The results suggest a need to explore the issue of role-specific terrorist profiles in more depth. To illustrate, McFate argues that it is imperative for researchers to examine the broader social environment in which bombs are ‘‘invented, manufactured, distributed and used.’’

This is mainly because improvised explosive devices are a product of human social organization. The individual planting a roadside bomb is often only the final node in a network of multiple actors fulfilling different role types. Each role type encompasses a specific number of functions for the IED to be created. Shifting our analytical gaze from ‘‘bomb’’ to ‘‘bomb-maker’’ (and bomb-maker affiliates such as component carriers, component procurer, component-storer, and IED transporters, etc.) should provide further insight into understanding how terrorist groups operate on the ground, how they are structured, and the typical antecedent behaviors that occur pre-attack.64

Conclusion

The database under analysis here will provide the basis of a fruitful research agenda. This article simply provided a descriptive analysis of our findings, but further research from this database will include social network analyses of particular PIRA Brigades and of the group as a whole across time, inferential investigations of role-specific terrorist profiles, a Brigade-level analysis on the capacity for creativity, and issues concerning recidivism and disengagement from militant groups.

This article provided the first systematic and holistic analysis of the Provisional

Irish Republican Army at the individual level of analysis. Methodologically, the article demonstrates that such large-N analyses are possible given the availability of resources and appropriate case selection. The research findings also demonstrate the necessity of such endeavors.

While much of American political science treats the analysis of terrorism and political violence at the event level, this article demonstrates the utility of a much more fine-grained micro-level approach. While dynamics such as counter-terrorism events and system-level variables are important in explaining the scale and intensity of non-state political violence, such analyses are incomplete

without an additional focus on micro-level factors such as the scale and

intensity of recruitment patterns and the constituent geographic and sociological

recruitment patterns that accompany them.

Micro-level approaches provide one strong means with which we can understand the key social, psychological, and cultural dynamics that underpin the broader processes that mobilize, characterize, and maintain any type of non-state political violence.65

A broader consequence of this lack of focus on micro-level issues to date is that much academic work on terrorism remains irrelevant for counter-terrorism practitioners and operators.

The findings in this article also provide relevant insight for the dynamics of contemporary groups. The older the cadre became, the less violent and more prone towards peaceful initiatives it also became. The surge in recruitment in particular geographic areas towards the ceasefire also may have provided a forewarning of what particular areas dissidents and splits were likely to emerge from.

While championing the cause of micro-level analyses, this article has also pinpointed a number of sub-fields that warrant attention, in particular issues concerning role types and the profile of individuals who engage in them.

Notes

1. The Irish Republican Army claims its descent from the Irish Volunteers, an organization that engaged in the 1916 Easter Rising. Following the Irish Republican Army’s formationin 1919, members were generally referred to as ‘‘volunteers.’’.

2. John Whyte, Interpreting Northern Ireland (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), vii.

3. Martyn Frampton, Legion of the Rearguard: Dissident Irish Republicanism (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2011); John Horgan and Paul Gill, ‘‘Who Becomes a Dissident? Patterns in the Mobilisation and Recruitment of Violent Dissident Republicans,’’ in Max Taylor and P. M. Curries, eds., Dissident Irish Republicanism (London: Continuum Press, 2011), 43–64; and John Horgan and John F. Morrison, ‘‘Here to Stay? The Rising Threat of Violent Dissident Republicanism in Northern Ireland,’’ Terrorism and Political Violence 23, no. 4

(2011): 642–699.

4. Robert White and T. F. White, ‘‘Revolution in the City: On the Resources of Urban Guerrillas,’’ Terrorism and Political Violence 3, no. 4 (1991): 100–132.

5. Marc Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004); F. Reinares, ‘‘Who Are the Terrorists? Analyzing Changes in the Sociological Profile Among Members of ETA,’’ Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 27, no. 6 (2004): 465–488; M. Florez-Morris, ‘‘Joining Guerrilla Groups in Colombia: Individual Motivations and Processes for Entering a Violent Organization,’’ Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 30, no. 7 (2007): 615–634; C. Fair, ‘‘Who Are Pakistan’s Militants and Their Families?’’ Terrorism

and Political Violence 20, no. 1 (2008): 49–65; A. Merari, Driven to Death: Psychological and Social Aspects of Suicide Terrorism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011); L. Clutterbuck and R. Warnes, Exploring Patterns of Behavior in Violent Jihadist Terrorists: An Analysis of Six Significant Terrorist Conspiracies in the UK (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation,

2011); Petter Nesser, ‘‘Profiles of Jihadist Terrorists in Europe,’’ in Cheryl Benard, ed., A Future for the Young: Options for Helping Middle Eastern Youth Escape the Trap of Radicalization (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2006), 31–49; and Edwin Bakker, Jihadi Terrorists in Europe, Their Characteristics and the Circumstances in Which They Joined the Jihad

(Clingendael Security Paper: Netherlands Institute of International Relations, 2006).

6. F. Reinares, ‘‘Who Are the Terrorist?’’ (see note 5 above).

7. Although there were increased factions through 1969 in PIRA over this issue, the formal split occurred over the issue of abstentionism when a vote was taken in December 1969 and January 1970.

8. R. English, Armed Struggle: A History of the IRA (London: Macmillan, 2003);

E. Moloney, A Secret History of the IRA (New York: Norton, 2003); T. P. Coogan, The IRA (New York: Palgrave, 2002); J. Bowyer Bell, The IRA, 1968–2000: An Analysis of a Secret Army (London: Frank Cass, 2000); H. Patterson, The Politics of Illusion: A Political History of the IRA (London: Serif, 1997); P. Taylor, Provos: The IRA and Sinn Fein (London: Bloomsbury, 1997); and P. O’Malley, Biting at the Grave: The Irish Hunger Strikes and the Politics of Despair (Belfast: Blackstaff, 1990).

9. S. O’Callaghan, The Informer (London: Corgi Books, 1999); E. Collins, Killing Rage (London: Granta Books, 1998); E. Moloney, Voices from the Grave: Two Men’s War in Ireland (New York: Faber and Faber, 2010).

10. Notable exceptions include Robert W. White, Provisional Irish Republicans: An Oral and Interpretative History (London: Greenwood Press, 1993), and Robert W. White, Ruairi O Bradaigh: The Life and Politics of an Irish Revolutionary (Indiana: IndianaUniversity Press, 2006). 454 P. Gill and J. Horgan

11. M. L. R. Smith, Fighting for Ireland: The Military Strategy of the Irish Republican Movement (London: Routledge, 1997), 145.

12. Moloney, A Secret History (see note 8 above), 513.

13. National Graves Association, Belfast Graves (Dublin: National Graves Association,

1985).

14. D. McKittrick, S. Kelters, B. Feeney, C. Thornton, and D. McVea, Lost Lives

(Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 2007).

15. Note that we only include arrests that subsequently led to convictions. For example, those arrested under internship were not added to the database unless a conviction was obtained.

16. Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks (see note 5 above).

17. Florez-Morris, ‘‘Joining Guerilla Groups’’ (see note 5 above).

18. Horgan and Gill, ‘‘Who Becomes a Dissident?’’ (see note 3 above).

19. Florez-Morris, ‘‘Joining Guerilla Groups’’ (see note 5 above).

20. Horgan and Gill, ‘‘Who Becomes a Dissident?’’ (see note 3 above).

21. Figures taken from English, Armed Struggle (see note 8 above), 379.

22. A. Silke, ‘‘Holy Warriors: Exploring the Psychological Processes of Jihadi Radicalization,’’European Journal of Criminology 5, no. 1 (2008): 99–123.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid., 107.

25. D. McAdam, ‘‘Recruitment to High-Risk Activism: The Case of Freedom Summer,’’The American Journal of Sociology 92, no. 1 (1986): 64–90; David A. Snow, Louis A. Zurcher Jr., and Sheldon Ekland-Olson, ‘‘Social Networks and Social Movements: A Microstructural Approach to Differential Recruitment,’’ American Sociological Review 45, no. 5 (1980): 787–801.

26. Former PIRA militant cited in R. Alonso, The IRA and Armed Struggle (London: Routledge, 2003), 11.

27. Ibid., 29.

28. Former PIRA militant cited in Moloney, Voices from the Grave (see note 9 above).

29. Coogan, ‘‘The IRA’’ (see note 8 above), 465–467.

30. M. Bloom, Bombshell: The Many Faces of Women Terrorists (Toronto: Penguin, 2011).

31. Moloney, Voices from the Grave (see note 8 above), 55.

32. For a fuller analysis of women within politically violent groups see L. Reif, ‘‘Women in Latin American Guerrilla Movements: A Comparative Perspective,’’ Comparative Politics 18, no. 2 (1986): 147–169.

33. O’Callaghan, The Informer; Collins, Killing Rage; and Moloney, Voices from the Grave (see note 9 above).

34. M. Bloom, P. Gill, and J. Horgan, ‘‘Tiocfaidh ar Mna: Women in the Provisional Irish Republican Army,’’ Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 4, no. 1 (2012): 60–76.

35. M. Dillon, The Dirty War: Covert Strategies and Tactics in Political Conflicts

(London: Routledge, 1999), 159–160.

36. Bloom, Gill, and Horgan, ‘‘Tiocfaidh ar Mna’’ (see note 33 above); S. Darragh, ‘John Lennon’s Dead’: Stories of Protest, Hunger Strikes and Resistance (Belfast: Beyond the Pale Publications, 2011).

37. Moloney, Voices from the Grave (see note 8 above), 108.

38. Ibid.

39. Coogan, ‘‘The IRA’’ (see note 8 above), 465–467.

40. McKittrick et al., Lost Lives (see note 14 above), 1559.

41. J. Horgan and M. Taylor, ‘‘The Provisional Irish Republican Army: Command and Functional Structure,’’ Terrorism and Political Violence 9, no. 3 (1997): 1–32.

42. Ibid., 8.

43. Ibid., 9.

44. Bowyer Bell, The IRA (see note 8 above), 520.

45. Moloney, Voices from the Grave (see note 9 above).

46. Horgan and Gill, ‘‘Who Becomes a Dissident?’’ (see note 3 above).

47. Horgan and Morrison, ‘‘Here to Stay?’’ (see note 3 above). Who Were the Volunteers? 455

48. White and White, ‘‘Revolution in the City’’ (see note 4 above).

49. P. O’Sullivan, ‘‘A Geographical Analysis of Guerrilla Warfare,’’ Political Geography Quarterly 2 (1983): 139–150.

50. Smith, Fighting for Ireland (see note 11 above), 145.

51. Coogan, ‘‘The IRA’’ (see note 8 above), 465–467.

52. For a firsthand account of the cell system’s introduction and its lack of implication in rural areas see T. McKearney, The Provisional IRA: From Insurrection to Parliament (London: Pluto Press, 2011).

53. Reinares, ‘‘Who Are the Terrorists?’’ (see note 5 above).

54. Fair, ‘‘Who Are Pakistan’s Militants’’ (see note 5 above).

55. Horgan and Gill, ‘‘Who Becomes a Dissident?’’ (see note 3 above).

56. Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks (see note 5 above).

57. White and White, ‘‘Revolution in the City’’ (see note 4 above).

58. S. Atran, Talking to the Enemy: Faith, Brotherhood and the (Un)making of Terrorists (New York: HarperCollins, 2011).

59. E. Bueno de Mesquita, ‘‘The Quality of Terror,’’ American Journal of Political Science 43, no. 3 (2005): 515–530.

60. Reinares, ‘‘Who Are the Terrorists?’’ (see note 5 above).

61. P. Gill and J. Young, ‘‘Comparing Role Specific Terrorist Profiles,’’ paper presented at the International Studies Association annual conference, March 2011.

62. Moloney, Voices from the Grave (see note 9 above), 20–24. PIRA planned for a dramatic escalation in violence during the late 1980s and likened this plan to the People’s Army of Vietnam’s ‘‘Tet Offensive’’ that began in 1968.

63. M. McFate, ‘‘Iraq: The Social Context of IEDs,’’ Military Review 85, no. 3 (May= June, 2005): 37–40, 37.

64. J. Horgan, Walking Away from Terrorism: Accounts of Disengagement from Radical and Extremist Movements (London: Routledge, 2009).

65. Ibid. 456 P. Gill and J. Horgan

TABLES

You must be logged in to post a comment.