A British military photo of the Divis Flats complex circa 1972/73 – All that remains today is the tower block on the centre left

Today myself and Anthony McIntyre are extending an invitation to members of Jean McConville’s family to join with us in lodging a Freedom of Information request at the British government’s archives at Kew in Surrey to obtain the release of the war diaries of the First Gloucestershire Regiment, which served in Divis Flats at the time, in early 1972, that Jean McConville allegedly came under IRA suspicion as an informer for the military.

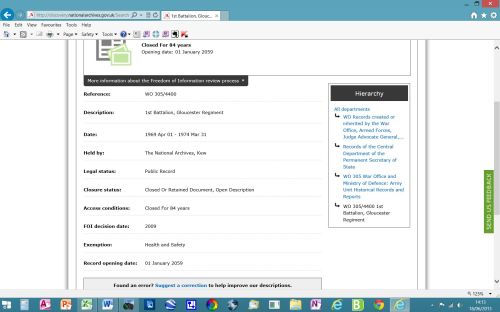

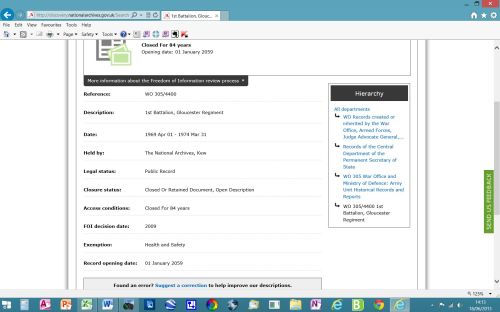

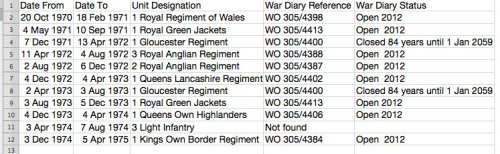

The First Gloucesters, one of the oldest and most battle hardened regiments in the British Army, was the only one of the nine regiments to have served in the Divis district of West Belfast during the early 1970’s whose war diaries have been embargoed and closed to the public, in that regiment’s case for an exceptional 84 years, until the year 2059. Under the 30 year rule the war diaries should have been made available by now but an extra embargo of over 50 years was imposed. It is our understanding that the British Ministry of Defence has the final say in such decisions.

The official embargoed notice at Kew on the war diaries of the First Gloucestershire Regiment

We are also planning to ask that the war diaries for 39 Brigade of the British Army, that is the Belfast command of the military, between August 1st, 1971 and September 30th 1971, and between June 1st 1972 and June 30th 1973 be opened for scrutiny. These documents have been embargoed for between 84 and 100 years.

We will be filing the requests in order to see if the war diaries, which are a daily account of a regiment’s military activity, contain any information which might indicate what happened to Jean McConville, the widowed mother of ten who was abducted from her apartment in the Divis Flats complex by the Provisional IRA in December 1972, taken across the Border to the Dundalk area, shot dead and her body secretly buried in a beach on the edge of Carlingford Lough.

In particular the request might settle for once and for all the question of whether the IRA killed Jean McConville because she worked as an intelligence source for the British Army.

Significantly, Nuala O’Loan, the former NI Police Ombudsman who investigated the Jean McConville ‘disappearance’ and whose report challenged suggestions that she had been a British Army informer, told thebrokenelbow.com in a phone interview this weekend that she had never heard of these war diaries until now.

She said that she would be ready to lend her support to our efforts to get the embargo lifted. “I am always ready for documents to be examined but I don’t know anything about them. I don’t know why they have been embargoed. I think I could be supportive of getting the documents out. I think there may be issues attached, there may have to be sections redacted. But I think that would be my only proviso.

Jean McConville with two of her children

We wish to stress that we are not conducting this exercise to prove that the IRA was telling the truth when it claimed that Jean McConville was killed because she was working for the British Army. We have enormous respect and understanding for the family’s view that their mother was killed and disappeared for reasons unconnected to any military exigency on the part of the IRA.

Nor do we wish our proposal to be regarded as an attempt to vindicate this heinous act by the IRA. What happened to Jean McConville was not only unjustified but was callous, cynical, barbaric and unnecessary and both of us are on public record repeatedly as saying so. I have also written that in my view her killing was a war crime; so has Anthony McIntyre. Strikingly, a significant number of former IRA activists have told me this is their belief also, and that they are ashamed that this act was carried out in their name.

There is no doubt either that certain key figures in the IRA of that time have lied about their part in Jean McConville’s disappearance and have done so repeatedly and grossly. Nor can there be doubt that such lying has infected the IRA’s account of Jean McConville’s death and the reason for her murder.

Gerry Adams denies all knowledge of Jean McConville’s disappearance

At the same time two credible IRA figures have come forward both to denounce that lying and also to say that her role as an informer was the reason Jean McConville was killed. Both Brendan Hughes and Dolours Price are now dead and cannot be quizzed about their versions of events but they both gave lengthy, credible and coherent accounts, Hughes in the book Voices From The Grave, which was derived from his interviews with Boston College, and Price in an interview with the Sunday Telegraph.

Dolours Price and Brendan Hughes

On the other hand, the former Northern Ireland Police Ombudsman, Nuala O’Loan has reported that from her inquiries in security circles she could find no evidence to verify the allegation that Jean McConville worked as an agent for the military or any other branch of the British security apparatus. But she has declined to go into detail and has, for instance, refused to say who in security world she spoke to or at what level.

No-one can doubt Nuala O’Loan’s integrity, nor that what she reported she genuinely believed to be the truth. But at the same time, if the IRA account is true, some in the British Army and others in the intelligence and political hierarchy may have had as much reason to lie and dissemble to the Police Ombudsman as does the IRA’s then Belfast leadership to the people of Ireland.

Remember Brendan Hughes’ account. According to his version, Jean McConville was uncovered as a spy when a radio transmitter was found in her apartment. According to Hughes she admitted her role when confronted with the evidence but because of her family situation, she was given a so-called ‘Yellow Card’ by Hughes and let go. But later the IRA discovered evidence she had resumed spying and that sealed her fate.

Nobody knows whether Brendan Hughes’ account is accurate but if it is, it means that the British Army continued to use as an agent someone whose cover had been blown, thus putting the agent’s life in great peril. And, if Hughes’ account is accurate, the army would have known Jean McConville’s cover was blown because her radio had been confiscated by the IRA.

If all this is true the British Army contributed significantly to the series of events that led to her murder. If all this is true the British Army acted recklessly and selfishly and was at least partly responsible for ten children losing their mother. If all this is true then British soldiers, possibly senior ones, had good reasons to lie and to keep these facts from the public and the McConville’s. And the McConville family have good reason to seek the maximum redress.

A daylight patrol in Divis by the First Gloucestershire Regiment (copyright: The Soldiers of Gloucestershire}

It should also be remembered that the British Army has a track record of telling lies, in one notorious case a massive lie, about its intelligence operations. When John Stevens, the former Cambridgeshire Deputy Chief Constable was sent to Northern Ireland in 1989 to investigate intelligence leaks to Loyalist paramilitaries he was told at a high level military briefing that the British Army ran no intelligence agents in Northern Ireland.

In fact, as he soon found out, the army not only ran agents but it had an entire dedicated detachment, the Force Research Unit, which did nothing else except run agents. The British Army lied then to cover up its role in the UDA murder of Pat Finucane; in such a context it is not inconceivable that they may have lied to cover up the death of Jean McConville.

So we have conflicting accounts, dead witnesses, lies told by one side and possibly lies told by the other. What we do not have enough of is truth that can be backed up by independent, contemporary evidence. That is why today we are announcing our plans to seek the opening of British Army files and asking the McConville’s to join us.

We are seeking only the truth. It may be that the files contain nothing of interest or significance and if that is the case, then so be it. It may be that the files support Nuala O’Loan’s suggestion that Jean McConville never worked for the British Army. It may be that they show she did but that her handlers exploited her and helped usher her to an early death. If that is the case, then so be it.

Over the past two years, the PSNI and the British government have sought to obtain interviews lodged in the archive of the Belfast Project at Boston College in their search for facts in the investigation of Jean McConville’s murder and disappearance. We also seek to obtain files lodged in the UK’s archives at Kew in our search for facts in the investigation of Jean McConville’s murder and disappearance.

With the appointment of Dr Richard Haass as the new US Special Envoy with the brief of charting a way to deal with the past, it is becoming clear that any effort to find out what happened during the Troubles will be fatally flawed unless there is absolute balance between competing sides, between paramilitary groups and security forces. The leadership of the Historical Enquiries Team is currently learning the hard way what happens when a process of investigating the past become tainted with double standards.

Richard Haass – new US Special Envoy to N

And so, if the PSNI is to be allowed access to Boston College’s files by the US courts, then we who were responsible for creating them should be allowed access to the British Army’s archive. Otherwise we have an investigatory process that is doomed to be one-sided and whose conclusions will be respected by only one part of the community. Such an outcome can only breed mistrust and further division.

So, why do we single out the First Gloucestershire Regiment in this Freedom of Information request?

The first reason has to do with the unusual act of requesting an embargo on the regiment’s war diaries and the length of that embargo, eighty-four years. This means that unless the embargo is successfully challenged the diary will not be opened until January 1st, 2059, by which time most of those reading this article will be long dead.

To put the embargo into context, it is the same length or just slightly shorter than the embargo placed on 39 Brigade war diaries at a time when the Brigade commander was Brigadier Frank Kitson and he was busy creating the Military Reaction Force (MRF), a super secret undercover unit which allegedly was involved in a series of drive by shootings and killings in Belfast.

In other words to qualify for an 84 year or 100 year embargo as 39 Brigade has, the activities in question need to be the sort that you really don’t want the world to know about, at least for a very long time, and long after those responsible have shuffled off this mortal coil.

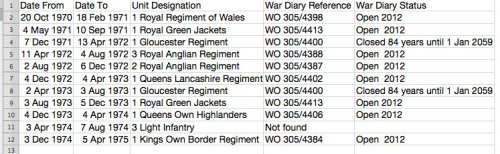

The full list of 39 Brigade embargoed war diaries is below. By contrast British Army brigade war diaries in Europe and Britain are open for public inspection:

So what was it that soldiers from the First Gloucestershire Regiment did in Divis Flats in 1972 and also in 1973 that they want hidden until 2059?

None of the other military units that served in Divis during these years felt that way. According to records compiled by our resourceful researcher Bob Mitchell, nine British regiments served in Divis Flats between October 1970 and April 1975. The list can be seen below in the graphic and it records that only one regiment cannot be traced in the Kew archive, the Third Battalion Light Infantry. Of the other eight, all can be traced and aside from the Gloucesters, none asked that its war diary(ies) be embargoed or were ordered by the MoD to be embargoed even though some of them, like the Royal Green Jackets and the Royal Anglian Regiment were posted to Divis during the worst periods of violence.

List of regiments that served in Divis in early 1970’s. The First Goucesters are the only unit whose war diaries have been embargoed until 2059. All the others are available for public inspection.

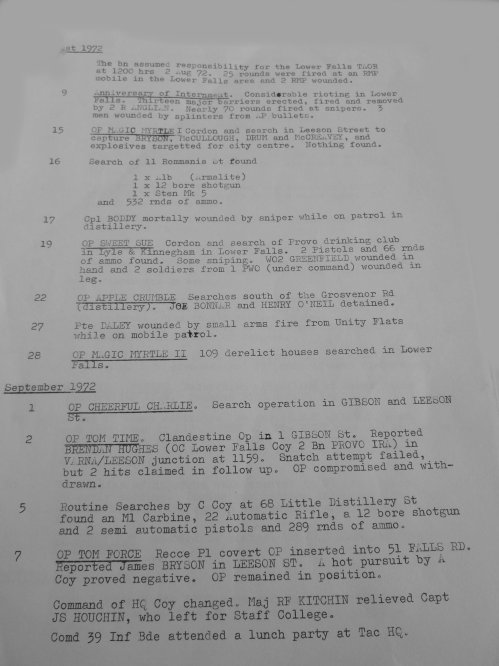

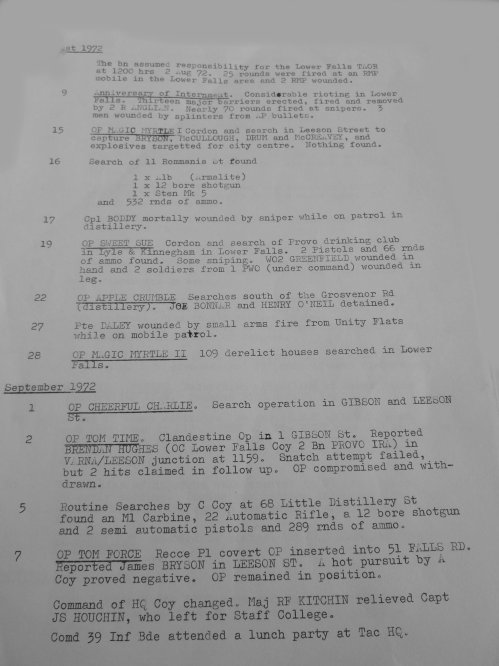

A war diary is a daily account of a regiment’s or Brigade’s activity during a tour of duty. This is a sample page fromn the Royal Anglin Regiment’s war diary for 1972.

So what was it that the First Gloucesters were involved in, in Divis Flats that made them so different from seven of their brother regiments?

Our research also brought us to journals and magazines produced by British regiments during the 1970’s which describe in sometimes fascinating detail their activities while posted to Northern Ireland. The Royal Green Jackets (RGJ) Chronicle is a particularly rich source of information.

The RGJ were posted to Belfast for the second time in August 1973 and a single company, ‘B’ Coy, was sent to Divis where, according to the account produced in that year’s Chronicle, priority was given to cultivating sources in the local population. While the Chronicle makes light of the way this was done, it seems that female residents of Divis were especially targeted. The account, which can be read in full below, concludes: “….by the end of the tour, all sections had established a friendly contact here and there.”

Extract from Royal Green Jackets Chronicle dealing with its tour of Divis Flats in 1973, between eight and twelve months after Jean McConville’s disappearance

So cultivating and recruiting intelligence sources from the population of Divis Flats, and possibly from female residents, appears to have been standard operating practice for British units, which common sense suggests would be the case. It is something the British would have done as a matter of course and not just in Divis.

A key part of Brendan Hughes’ story concerned the radio that was allegedly discovered in Jean McConville’s flat and with which she is supposed to have communicated with her handlers in Hastings Street RUC station which had become the British Army’s local HQ. In his interview with Boston College, Hughes did not describe the radio in any detail but it appears that it was what most people would know as a walkie-talkie type radio, small and compact, easy to hide and use.

The problem is that some people have raised doubts about whether the British Army had access to such equipment in the early 1970’s and that the only radios in use at that time were heavy, bulky sets totally unsuitable for use by an agent such as Jean McConville. In fact that is not true and the source for this is the Saville report on the Bloody Sunday killings of January 1972.

Paragraph 181.13 of the report reads:

“We should also record that there is evidence that before Bloody Sunday some of the resident battalions were, at platoon level only, using portable Stornophone radios in place of Larkspur radios. A number of former soldiers serving in Londonderry recalled having Stornophone radios available on 30th January 1972. Often nicknamed “Stornos”, these radios, like the Pye radios discussed above, were a commercially produced system purchased by the Army. There is little doubt that the use of Stornophone radios was a consequence of the fallibility of Larkspur radios in built-up areas.”

Stornophone radios were ideal for agent use. Manufactured by the Norwegian Storno Company, the average set was 10” long. 2.5” wide and 1” thick, it had a rechargeable battery pack and a simple ‘push to talk’ operation. The question then is whether Stornophone radios were available to British troops in Divis in early 1972 and the answer is yes.

The bulky Larkspur radio, totally unsuitable for agent use

The Norwegian made Stornophone radio, available to some platoons in NI in early 1972. Very agent friendly.

The answer comes from the ‘Soldiers of Gloucestershire’ website, which is dedicated to all things to do with the Gloucestershire Regiment, including a massive collection, dating back to the 18th century, of paintings, prints and photographs of the regiment during its various campaigns and wars, including its various tours to Northern Ireland.

One photograph shows a soldier from the Gloucesters on patrol in Divis Flats in 1972 holding and maybe using a Storno-type hand held radio.

Here is the photo:

A soldier from the First Gloucesters uses a Stornophone type radio while on patrol in Divis Flats in April 1972 (Copyright: The Soldiers of Gloucestershire)

So a hand held walkie-talkie type radio of the sort that Brendan Hughes said was found in Jean McConville’s flat was in use by soldiers from the First Gloucestershire regiment in Divis Flats in 1972, the year she was abducted & killed, and the war diary for that tour has been embargoed until 2059. A cloud now hangs over the Gloucestershire regiment which can only be dispelled by full disclosure of the unit’s archives.

There is one final issue that arises out of the Police Ombudsman’s report on Jean McConville’s disappearance. It derives from a section of her report dealing with intelligence reports on the whereabouts of Jean McConville after she disappeared from Divis. That section was summarised in a press release dated August 13th, 2006 from the Police Ombudsman’s office. Here is the relevant section:

“There is no intelligence about or from Mrs McConville until 2 January 1973. An examination of RUC intelligence files show that the first intelligence was received on January 2 1973 when police received two pieces of information which said that the Provisional IRA had abducted Mrs McConville.

“On January 16 1973, Mrs McConville’s disappearance and the plight of her children were reported in the media. A police spokesman was quoted as saying that although the matter had not been reported to them, it was being investigated.

“RUC intelligence files show that the next day police received two pieces of information about the disappearance: One claimed that Mrs McConville was being held by the Provisional IRA in Dundalk. The other also alleged that the Provisionals were behind the abduction and suggested it was related to drug dealing.

“The RUC intelligence files also show that the police later received two separate pieces of information from military sources which suggested that Mrs McConville was not missing: The first was received on March 13 1973 and suggested that the abduction was an elaborate hoax. The second piece of information, which was received 11 days later, said that Mrs McConville had left of her own free will and was known to be safe.”

There is a clear pattern here. Intelligence coming in to the RUC in the first weeks after her disappearance was remarkably accurate. The Provisional IRA had abducted her. Check. Jean McConville was being held in Dundalk. Check. A second report again said that the Provisonals had abducted her. Check. The same report claimed a drug connection which was clearly wrong. But this is the only piece of inaccurate intelligence coming into the RUC at this time.

But then in mid-March the story changes dramatically. Two separate pieces of intelligence from military sources throw cold water on the abduction explanation. One, on March 13th, says that the story of Jean McConville’s kidnapping was “an elaborate hoax”. A second report on March 24th claimed she had left Belfast of her own free will and was safe.

Former NI Police Ombudsman Nuala O’Loan

So who were these military sources? Nuala O’Loan does not tell us. But here is an interesting coincidence. On April 2nd, 1973 the First Gloucestershire Regiment arrived in Belfast for a four month tour – their second since late 1971, early 1972 – and two days later took over duties from the Queens Lancashire Regiment.

It was standard operational procedure for advance parties to arrive several weeks ahead of the main regimental force and included in them would be an intelligence unit. This was done so that the new regiment would be able to ease in to its new duties. So an intelligence unit from the 1st Gloucesters would likely have been in West Belfast when those reports were sent to the RUC saying that Jean McConville was safe. Did the 1st Gloucesters create those intelligence reports or have any hand in them? We don’t know. Perhaps the information is contained in those embargoed War Diaries. That’s another reason they should be opened.

As I say, the war diary may reveal absolutely nothing about Jean McConville at all, in which case her surviving family have everything to gain by knowing this. And so do the First Gloucesters, whose name deserves to be cleared if the regiment is innocent of any suspicion attached to it.

But if the diary does reveal information that the family would probably regard as unwelcome then they and everyone else will have to deal with it. We need to know the truth about what happened to Jean McConville. Hiding facts behind embargoes is unacceptable when others are being forced by legal measures to disclose theirs. Equally, lying about the past by those involved in these events is as intolerable as continuing to exploit an agent whose cover has been blown.

One way or another we need to know what is written in the embargoed War Diaries of the First Gloucestershire regiment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.