By James Kinchin-White and Ed Moloney

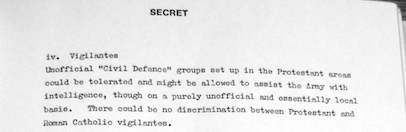

OFFICIAL PAPERS FROM 1971 SHOW THE HEATH CABINET AGREED A POTENTIAL INTELLIGENCE RELATIONSHIP WITH ‘PROTESTANT VIGILANTES’ – ‘CIVIL DEFENCE’ GROUPS COULD BE ‘TOLERATED’ – DEALINGS WOULD BE ‘UNOFFICIAL & LOCAL’

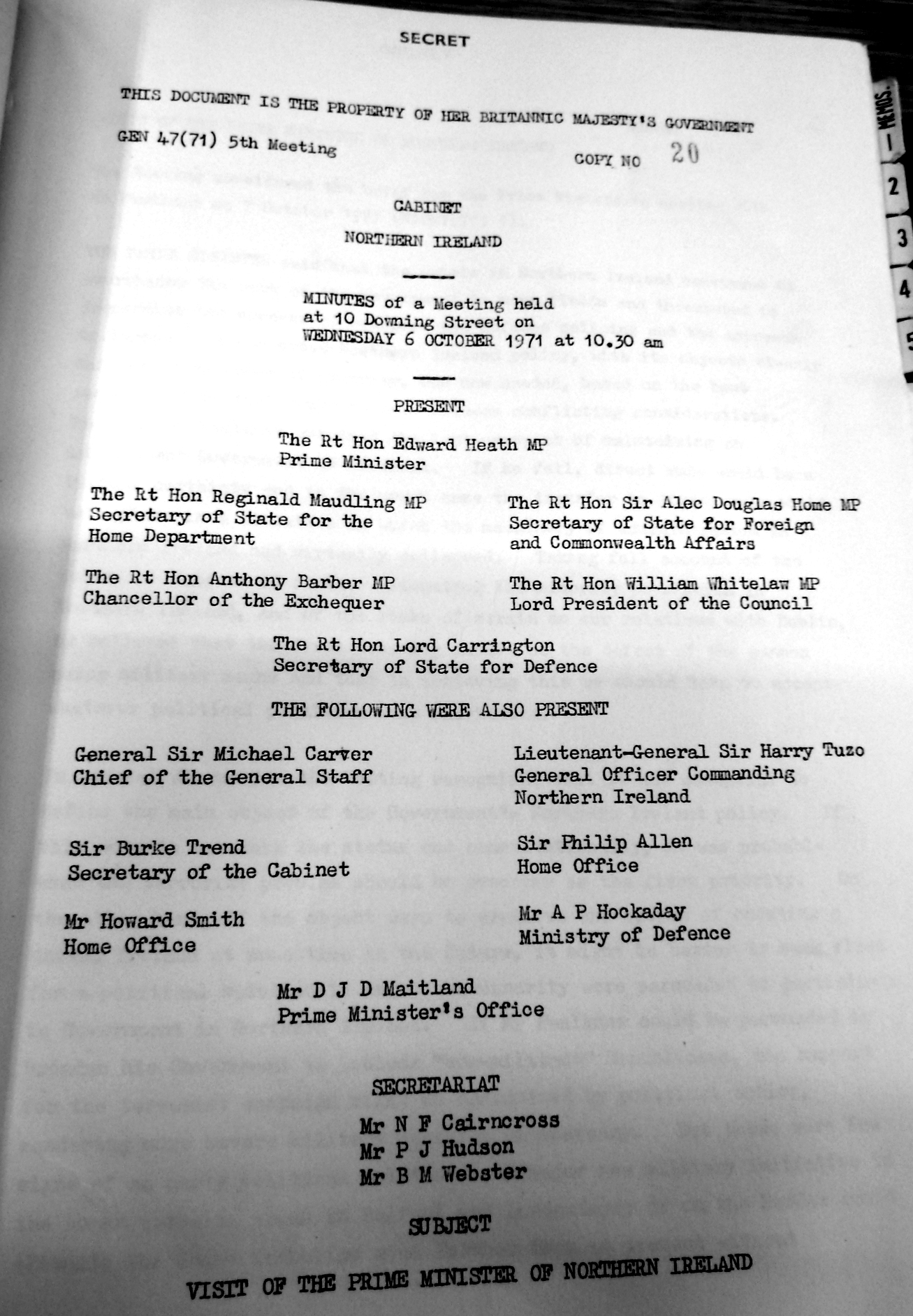

At 10:30 a.m. on October 6th, 1971 the most senior members of the British cabinet, headed by prime minister, Ted Heath met at Downing Street with only one item on the agenda: the deteriorating security and political situation in Northern Ireland. To underline the gravity of the situation facing the British, only those with a stake in the crisis or its possible consequences were invited. Prime Minister Heath presided of course; the ministers present were the real makers and shakers in the British government: the Home Secretary Reginald Maudling; Foreign Secretary Sir Alec Douglas Home; the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Anthony Barber; Lord President of the Council, William Whitelaw and the Defence Secretary, Lord Carrington.

British prime minister Ted Heath outside 10 Downing Street

Together they made up a group known as GEN 47, in effect a Cabinet sub-committee whose specific responsibility was Northern Ireland policy. The meeting that October morning was the fifth held since the committee was formed. The two most senior officers in the British Army responsible for the security situation in Northern Ireland were also at the table: the Chief of the General Staff, General Sir Michael Carver, who was the head of the British Army, and the GOC in NI, Lt-General Sir Harry Tuzo. Alongside them sat the key officials dealing with the crisis, including future MI5 chief, Howard Smith who was the UK representative in Belfast, and the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Burke Trend.

22nd March 1972: Brian Faulkner, the last Stormont Prime Minister of Northern Ireland arriving at Downing Street for talks with Edward Heath. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

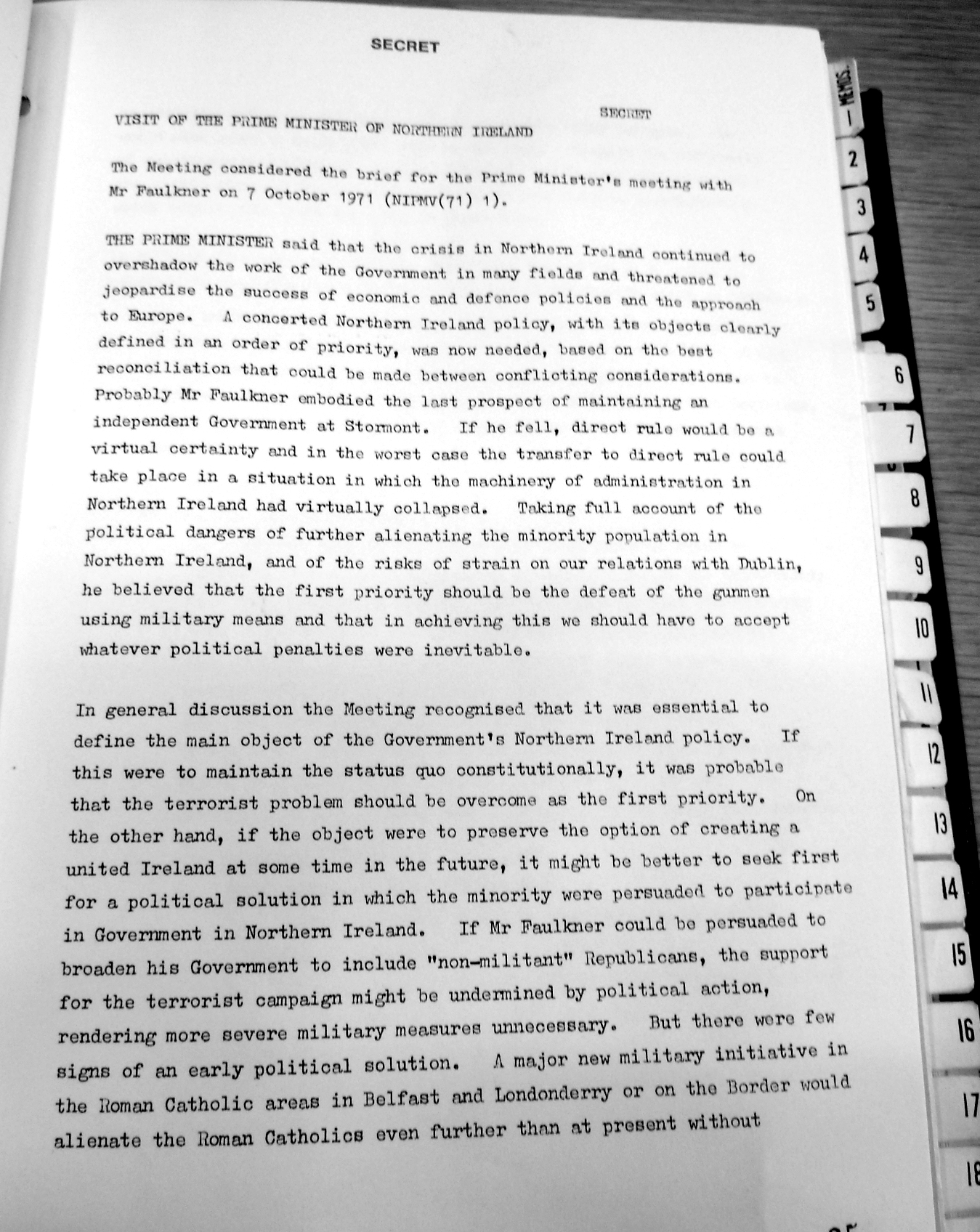

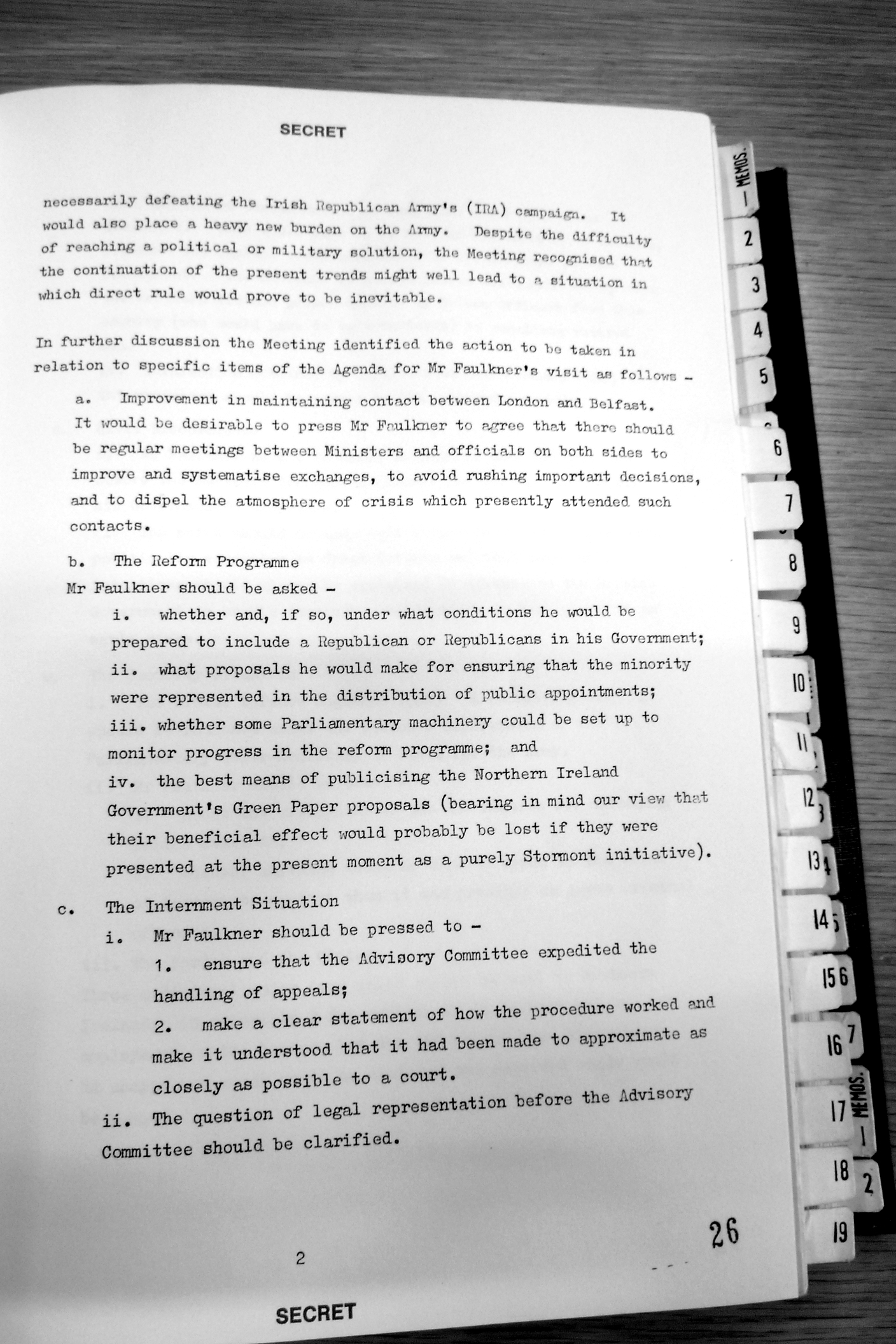

Two months before, on the advice and urging of the Stormont prime minister, Brian Faulkner, the British Army had rounded up hundreds of alleged IRA suspects from Nationalist areas of the North with a view to interning them. Faulkner had assured the British that internment had worked when he was Home Affairs minister in 1956 and it would work again. Internment had killed off the IRA’s Border campaign and it would do the same to the new Provisionals. He was wrong. The British Army had moved against the IRA before intelligence on the new Provisional organisation was fit for purpose – a strategem credited by the late Brendan Hughes to Gerry Adams in confidential interviews for ‘A Secret History of the IRA’. Adams had advocated an intensification of bombings in the early months of 1971, thereby causing a clamor for action from angry Unionists and an intemperate response from the British. And the operation was so one-sided, completely ignoring Loyalist violence, that the effect was to alienate almost the entire Catholic population, leading to resignations from public office and withdrawals from public bodies. The SDLP, Britain’s sole hope of Nationalist moderation, was swept along by the wave of anger and vowed not to engage the British until internment was ended. Worst of all the violence had not abated, as was evident daily, especially in Belfast where shootings, bombings, killings and attacks on the military and police had escalated alarmingly. The purpose of the meeting was to agree on the cabinet’s attitude towards Faulkner, who ministers were painfully aware was the only person standing between the Stormont government and the perilous, uncharted waters of direct rule. If the Unionist prime minister was in consequence hoping for a sympathetic hearing, he was to be disappointed. Heath’s opening remarks and the subsequent account of the meeting were peppered with phrases like, ‘…if Mr Faulkner could be persuaded….’; ‘It would be desirable to press Mr Faulkner to….’; ‘Mr Faulkner should be asked…’; ‘Mr Faulkner should be pressed…’, ‘Mr Faulkner should be told….’, and so on.

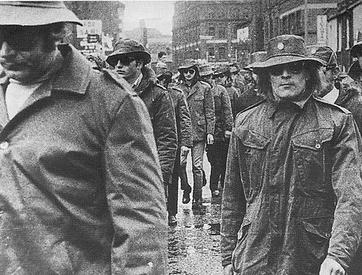

Riots exploded in Nationalist areas in the wake of internment

The polite Whitehall mandarinese employed by Heath and his ministers could not disguise a not so subtle subtext which must have deeply unsettled the Unionist leader: ‘You are running out of time, so you better listen to what we say.’ Heath’s prime concern was evident in his opening words:

…the crisis in Northern Ireland continued to overshadow the work of the government in many fields and threatened to jeopardise the success of economic and defence policies and the approach to Europe. A concerted Northern Ireland policy, with its objects clearly defined in an order of priority, was now needed, based on the best reconciliation that could be made between conflicting considerations.

Britain’s vital national interests were being threatened by the deteriorating situation in Northern Ireland and big decisions would soon have to be taken, not least about Brian Faulkner’s future Of particular concern to Heath was that the UK’s imminent accession to the EEC was on a knife edge. Parliament was bitterly divided and Heath would need the eight Unionist votes in the House of Commons to ensure success. But for that consideration it is possible that the GEN 47 meeting that morning would have been considering the arrangements for direct rule and Brian Faulkner would have been out of a job. Instead it became an occasion to strong arm the Unionist leader.

Smiling faces disguised a tough message from Heath to the Unionist prime minister Brian Faulkner

Direct rule would eventually be imposed in March 1972, six weeks after Heath won his EEC vote at Westminster. The margin of his victory in the Commons? Eight votes. Back in October 1971, the choice was simple. Opt to eliminate the IRA with a military offensive and implicitly back the Unionists and the Union – but at the cost of deepening Nationalist alienation, angering the government in Dublin and alienating European allies; or try to persuade Faulkner to include moderate Nationalists/Republicans in government, a course which might pull the sting from the IRA’s tail and satisfy Britain’s critics in Dublin and Brussels. It is clear where the cabinet’s heart lay, if only by the number of words devoted to the latter option and the list of demands that would be presented to Faulkner when he met his British counterparts. The clinching argument? Perhaps this:

‘If Mr Faulkner could be persuaded to broaden his government to include “non-militant” Republicans, support for the terrorist campaign might be undermined by political action, rendering more severe military measures unnecessary.’

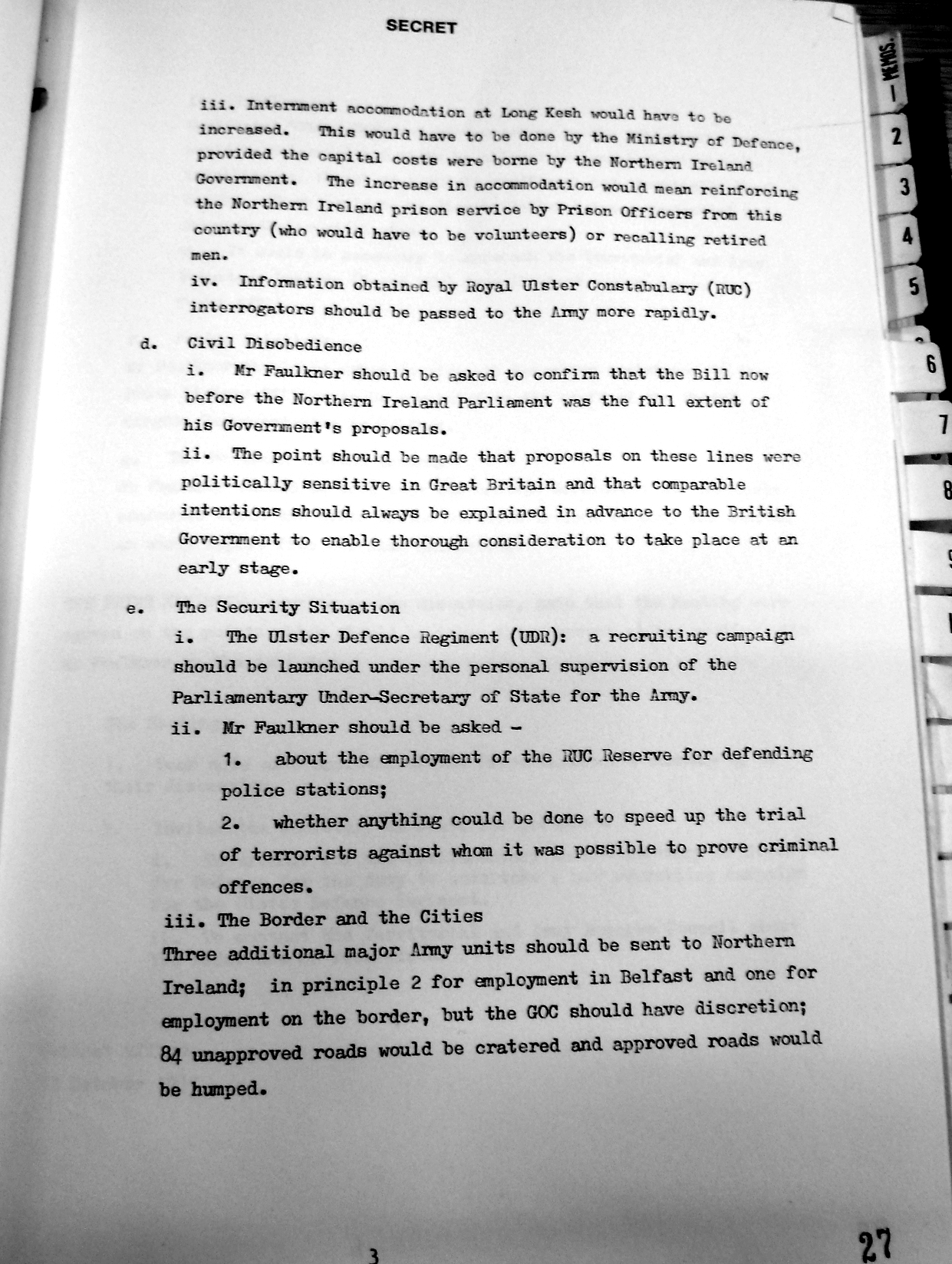

There were more demands on Faulkner: Would he appoint more Catholics to public posts? The reform programme needed monitoring, would he help to do that? And the internment policy needed to be fine tuned; the appeals procedure required improvement and clarification; accommodation at Long Kesh had to be improved albeit at Stormont’s expense not Westminster’s. And the RUC was slow in handing over intelligence acquired during interrogations to the military; could that be speeded up? A law confiscating social security payments to punish civil disobedience in protest at internment had embarrassed the British government at home and abroad, and such matters should be the subject of prior consultation in the future. And so on. It is difficult to read the GEN 47 document and not conclude that British ministers had exhausted their patience with the Unionist leader and that it was only a matter of time before direct rule had to be imposed. The Cabinet meeting of October 6th was the preamble to cutting the cord with Unionism as it had existed since 1921. Britain had not occupied Ireland for the best part of seven centuries nor created an empire which stained the globe red for some 200 years by not knowing when it was to her advantage and in her interests to abandon a chieftain or turn against a maharajah, no matter how loyal or useful such subjects had been in the past. And so Brian Faulkner’s destiny was set that October mid-morning.

In the summer of 1972 the UDA took to the streets of Belfast in force

But even as the British readied themselves to discard traditional Unionism, the Heath cabinet tacked back, for reasons that even now are not clear. Self-interest clearly dictated the move, but whether this was motivated by security needs or political necessity born of the knowledge that Stormont would soon be dissolved and Unionist anger would have to be appeased, can only be guessed at. After listing security requirements like stepping up recruitment to the UDR, increased use of the RUC Reserve, speeding up terrorist trials and cratering/humping Border roads, the Cabinet meeting advanced this extraordinary proposal, which reads:  So at this Cabinet meeting, whose record has been retrieved from the Kew archive (see below), the British government set in motion the process of hanging their erstwhile ally, Brian Faulkner out to dry while turning to the Loyalist ‘vigilantes’, as the Cabinet report called them, then beginning to organise and mobilise in Northern Ireland for assistance, deciding that they could be ‘tolerated’ and even approached for assistance with ‘intelligence’, presumably on the IRA. All done ‘unofficially’, of course and at a purely local level.

So at this Cabinet meeting, whose record has been retrieved from the Kew archive (see below), the British government set in motion the process of hanging their erstwhile ally, Brian Faulkner out to dry while turning to the Loyalist ‘vigilantes’, as the Cabinet report called them, then beginning to organise and mobilise in Northern Ireland for assistance, deciding that they could be ‘tolerated’ and even approached for assistance with ‘intelligence’, presumably on the IRA. All done ‘unofficially’, of course and at a purely local level.

THE FULL TEXT OF THE GEN 47 REPORT ON UK CABINET MEETING OCT 6, 1971

So what happened to this proposal? Why was it made? And from where did it emanate? It is easier to suggest an answer to the second and third questions than the first. The story begins a month before GEN 47 met, when, in early September 1971, the GOC, Lt-General Tuzo met with members of the Ulster Special Constabulary Association (USCA), at their request, one of a series of meetings the former part-time policemen cum paramilitaries held with British and Unionist leaders during this turbulent, post-internment period. The USCA was comprised of former “‘B’ Men”, as everyone in Northern Ireland called them, who had been angered at the British government’s decision in 1970 to disband the force. In their place, two new bodies, the RUC Reserve and the Ulster Defence Regiment, would be created, into whose ranks Catholics would be welcomed. The ‘B’ Specials had been in existence for as long as the state of Northern Ireland and were created as a reserve force to be called up for active duty if and when the threat from the IRA was considered serious by the Unionist government. The ‘B’ men were mobilised in 1922 and again during the 1956-1962 IRA Border campaign. Whatever about the IRA campaign from 1922 onwards, most observers credited lack of Catholic support for the IRA’s failure in the Border campaign, but the USCA firmly believed – and boasted – that they alone had defeated the IRA. Membership was exclusively Protestant and having been drawn in no small part from the ranks of Carson’s Ulster Volunteers at inception, its rank and file were considered fierce Loyalists whose sectarian sympathies and hostility to Catholics were defining features. Many if not most Catholics regarded the ‘B’ men as Unionism’s armed wing and feared/hated them accordingly.

So what happened to this proposal? Why was it made? And from where did it emanate? It is easier to suggest an answer to the second and third questions than the first. The story begins a month before GEN 47 met, when, in early September 1971, the GOC, Lt-General Tuzo met with members of the Ulster Special Constabulary Association (USCA), at their request, one of a series of meetings the former part-time policemen cum paramilitaries held with British and Unionist leaders during this turbulent, post-internment period. The USCA was comprised of former “‘B’ Men”, as everyone in Northern Ireland called them, who had been angered at the British government’s decision in 1970 to disband the force. In their place, two new bodies, the RUC Reserve and the Ulster Defence Regiment, would be created, into whose ranks Catholics would be welcomed. The ‘B’ Specials had been in existence for as long as the state of Northern Ireland and were created as a reserve force to be called up for active duty if and when the threat from the IRA was considered serious by the Unionist government. The ‘B’ men were mobilised in 1922 and again during the 1956-1962 IRA Border campaign. Whatever about the IRA campaign from 1922 onwards, most observers credited lack of Catholic support for the IRA’s failure in the Border campaign, but the USCA firmly believed – and boasted – that they alone had defeated the IRA. Membership was exclusively Protestant and having been drawn in no small part from the ranks of Carson’s Ulster Volunteers at inception, its rank and file were considered fierce Loyalists whose sectarian sympathies and hostility to Catholics were defining features. Many if not most Catholics regarded the ‘B’ men as Unionism’s armed wing and feared/hated them accordingly.

British Army GOC, General Sir Harry Tuzo – his response to the GEN 47 project was not recorded but he is the probable author of the proposal for an intelligence relationship with ‘Protestant Civil Defence’ groups

It is important to note what was going on when Tuzo met the USCA. Internment had just happened but was widely judged not just a political disaster but a security failure. It was directed solely at Republicans and civil rights leaders but it had failed to shut down the IRA, principally because British intelligence on the new Provisionals was so dated. So, in September 1971, it is likely that Tuzo would have been open to any suggestions that could rectify this alarming intelligence deficit. We do not know what the USCA said to Tuzo but we can guess. In April 1980, to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the disbandment of the ‘B’ men, the USCA published a 70 page pamphlet extolling the virtues of the Special Constabulary. The pamphlet’s principal claim was that its members’ special local knowledge and military skills would have been effective tools against the IRA but these had been squandered thanks to the decision to disband the force. This extract from the pamphlet tells a story in terms that the USCA had probably repeated to Tuzo:

They were no worse trained than the average British soldier, they numbered in their ranks many ex Servicemen, and their instructors included many of the finest instructors who had ever attended the military small arms schools at Hythe and Netherhaven. They were not armed with sophisticated modern firearms, but they were proficient in the use of the obsolete and obsolescent British military small arms with which they were issued. It was their proud boast that they had defeated on many occasions Army marksmen in annual competitions at Ballykinlar. They had no electronic or communication equipment, they had no armoured cars and their transport was more often than not their own private cars, they had no protective clothing, but they did have definite advantages over the modern soldier now patrolling Ulster’s streets and ditches. They possessed absolute confidence in their superiority over the IRA, and they were sure in the knowledge that the IRA recognised that superiority and feared it, but above all their roots were firmly bedded in Ulster soil giving them a native wit, intelligence and local knowledge which no amount of training or education could acquire. In any initiative taken they enjoyed the full support of the local community, something which militarily, is impossible to achieve. There is no doubt that given proper tasking and leadership from within themselves, the Ulster Special Constabulary would have so inhibited the movement of the IRA that the number of murders committed by any terrorist or paramilitary group would not have been as high as it is, the destruction of urban areas would not have been as great, and this campaign of terror would not have lasted for ten years.

It is not difficult to imagine General Tuzo, in the aftermath of a mostly failed internment operation against the Provisional IRA, listening to a presentation like this and thinking to himself that it might be no bad thing for the British Army to have access to assistance from people like these former ‘B’ Specials. He might even have been tempted to echo this claim made in the same pamphlet:

How often has it been said in Ulster homes, in Army messes, and even in the corridors of Westminster, that the disbanding of the Ulster Special Constabulary was a mistake.

B Specials in training – the force was mobilised against the IRA in 1922 and again in 1956

There is another reason to suppose that Tuzo was the author of this proposal at the GEN 47 meeting. At the time that he agreed to connect with the USCA, Tuzo brusquely dismissed a similar request from a group called the Catholic Ex-Servicemen’s Association (CESA), saying that he did not have the time to meet them. Although now largely forgotten, the CESA was, briefly, an important player on the Nationalist wing of the Troubles stage in the very early years. Comprised of Catholics who had served in the British Army, CESA attracted at its peak thousands of members who volunteered to protect Catholic areas in Belfast and elsewhere that were under threat from Loyalist paramilitaries and the British Army. Although separate from the Provisional IRA – and in some ways even unfriendly to Republicans – many Unionists and not a few British military leaders regarded CESA in the same hostile light as they did the IRA. In May 1972, for instance, the MRF shot dead a CESA member, Patrick McVeigh as he manned a barricade in west Belfast. And documents retrieved from the Kew archive reveal that the British often regarded CESA as indistinguishable from the IRA. (You can read much more about the origins and history of CESA on this ‘Treason Felony‘ blog post.) Tuzo’s refusal to meet CESA while agreeing to sit down with the USCA was a pretty blatant act of political favoritism, bigotry even, and GEN 47 implicitly acknowledged that by singling out the need to avoid such partisanship in the future dealings in such matters, a message clearly directed at the GOC:

There could be no discrimination between Protestant and Roman Catholic vigilantes.

This part of the GEN 47 report was both a rap on Tuzo’s knuckles and an implicit admission that the GOC was the probable author of the broader proposal for an intelligence relationship with Loyalist groups. It is also important to place the GEN 47 proposal in the context of events in the wider world of Northern Ireland Loyalism in the autumn of 1971. Against a background of the initial failure of internment and the upsurge of violence thereafter – sixty violent deaths in the five months after August 9th, compared to 31 in the seven months prior – alarmed and angry Unionists intensified their calls for a ‘Third Force’, in effect a sort of re-born ‘B’ Specials-type outfit. The new Ulster Defence Regiment was distrusted and disliked because it had been formed to replace the beloved ‘B’ men, and because places were reserved for Catholics who were, at least initially, joining up. How could Catholics defend Ulster, asked angry Loyalists? In early September, the USCA pledged its membership to such a force and later invited ‘all able-bodied’ men to register for a re-formed special constabulary. At the same time Ian Paisley and former Unionist Home Affairs minister, Bill Craig – the pair now established as Faulkner’s strongest Unionist critics – held a rally in east Belfast demanding the creation of a new ‘Third Force’ to defeat the IRA. (The British Army and the RUC were the first and second forces, the new body of Loyalists would be the third.)

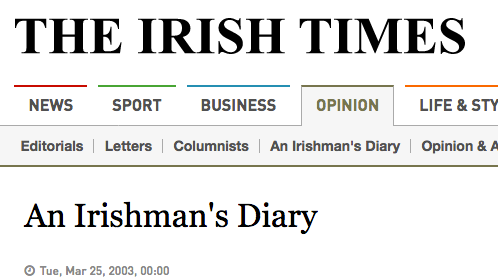

Ian Paisley (left) and Bill Craig (far right)

The crowd, which gathered at Sydenham, mid-way between the Harland and Wolff shipyard and the Shorts aircraft factory, was estimated at 20,000 strong. Afterwards a deputation from the shipyard and the aircraft factory met Tuzo at Thiepval barracks to press home the demand. So the GOC had now heard the same message from two sets of Unionism’s hard men. Paisley then held rallies around the countryside to urge Protestants willing to serve in the new ‘Third Force’ to hand in their names. The USCA met Faulkner around the same time to press home the demand for a ‘Third Force’ and one of Faulkner’s more populist ministers, John Taylor announced his support for such a body (in a not unrelated act a few months later, the Official IRA came close to assassinating him). At another rally, this time in the Unionist heartland of Portadown, Co Armagh, Ian Paisley unveiled a name for the new force: ‘Ulster Loyalist Civil Defence Corps‘. The next day Bill Craig endorsed it. Faulkner was under pressure from Unionist hardliners, not a few of whom were in his own party’s ranks, but conceding the demand for a new Third Force was a bridge too far for the British. Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling, who had ultimate responsibility for Northern Ireland prior to direct rule, declared his opposition to the idea and said that anyone who tried to set up such a body would be stopped by the government in London. But before Maudling’s statement, the British Ministry of Defence announced plans to allow the Ulster Defence Regiment to create units that would allow part-time members to serve close to their homes. As concessions go, this one hardly rated. By the time the GEN 47 committee met, there was real pressure on the British to placate the growing Loyalist clamour for action against the IRA. The Heath cabinet also knew that Stormont would soon be put on ice and that there would certainly be an angry, even violent response from hardline Loyalists. Some might even turn their guns on the British. So granting a concession like the intelligence aid suggested by GEN 47 might take some of the sting out of what was always going to be a difficult, even violent change. This is a story replete with questions but short on answers. The key question is whether the GEN 47 decision was ever implemented and if so by whom and how? Another comes a close second: if the proposal was followed up, which groups were chosen by the British Army as suitable partners in such an enterprise? The obvious candidates were groups like the USCA and the plethora of similar but small groups that would spring up a few months later when direct rule was imposed and the Stormont parliament mothballed. But there was another organisation that formally took its place on the Loyalist stage in that turbulent month of September 1971, an outfit that very soon would become the loudest voice of Loyalism and one of the most violent. It would have been extraordinary had the emergence of this group not been on Tuzo’s mind as he sat at the Cabinet table for the GEN 47 meeting. According to most dependable accounts, the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) was conceived at a meeting held in mid-May, 1971 of defence or vigilante groups drawn from various Protestant parts of the city. The gathering was held at a school canteen at the Loyalist end of North Howard Street, which linked the Nationalist Falls Road and the Loyalist Shankill Road, as Belfast’s two most infamous streets almost crosscut into the city centre. Alarmed at the growth of IRA violence, the meeting had been convened to examine the possibility of merging the various groups in a single, strong organisation. The gathering ended with an agreement to do just that; the name chosen was the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), a structure and leadership was put together but it was not until September that year, that the new group showed itself publicly. The UDA will take its place in the history of the Troubles as second only to the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) as the most violent of the Loyalist paramilitaries. But in its first couple of years of life, when admissions of murder were few and far between – and when the RUC preferred to call the random killing of Catholics ‘motiveless murders’ – the UDA was better known for staging huge marches and demonstrations in Belfast and other Loyalist areas, designed to show the British what resistance they could face if hardy came to hardy. Marches/protests, as well unofficial roadblocks and night-time patrols – which the UDA organised in their areas – were what ‘civil defence’ groups would do.

Would the GEN 47 proposal have allowed an ‘intelligence relationship’ between these soldiers and the Loyalists marching past them?

Coincidentally or not, the UDA’s emergence corresponded with the growing call from the Unionist heartland for a ‘Third Force’; but the question remains, did this new group qualify as a ‘vigilante’ or ‘unofficial civil defence’ group in the eyes of GEN 47 and the British military. Could or would the British Army reach out to the UDA for unofficial intelligence assistance in the way now apparently possible for other groups such as the USCA? On one reading, the answer might be yes. For instance, Sidney Elliott and W.D. Flackes in their indispensable guide to the Troubles, ‘Northern Ireland – A Political Directory, 1968-1999‘, reflect a widely held media and academic view of the UDA at the time of its birth that places it in the same category as the USCA and arguably qualifies it for GEN 47’s criterion for ‘civil defence’. Opinions like this would both reflect and reinforce official positions in government:

The UDA was launched in September 1971 as the umbrella body for loyalist vigilante groups, many of which called themselves ‘defence associations’. In the growing violence, they sprang up in Protestant areas of Belfast and in estates in adjoining areas, including Lisburn, Newtownabbey and Dundonald. The new body adopted the motto ‘Law before violence’, and soon became a formidable force on the ground in loyalist districts, in many of which it was considered a replacement for the disbanded B Specials.

On the other hand, the UDA was soon wading in blood and that would – or should – have placed it in a different category. However when the GEN 47 committee convened in London, the UDA had been responsible for just 4 deaths (including two UDA men killed by their own bomb). And because of a policy never to claim killings, unlike the IRA which invariably admitted its violence, it was never clear when the UDA had murdered people. The following year the UDA killed 72 people – one every five days and the reality that lay behind this particular ‘civil defence’ group was bloodily apparent. But there were few claims of responsibility made for sectarian murder in those early days. The authorities might know, and the UDA itself certainly knew – but the world was fed a version in which the killers went unnamed. Inside Northern Ireland, there were few illusions; most Catholics, and certainly a large number of Protestants knew full well what was happening but officially and, sadly, in large sections of the media, fiction became fact or at most disputed fact. In 1973 the UDA invented a cover name – the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF) – giving birth to a group which did not exist in any meaningful way; that the British went along with this fiction by proscribing the UFF but leaving the UDA untouched (until 1992 when arguably it no longer mattered) was revealing of both intentions and attitude. (Incidentally, within two years the USCA, along with other groups like the Orange Volunteers and Down Orange Welfare would join the UDA – and the illegal UVF/Red Hand Commando – in the Ulster Army Council, to co-ordinate activity against the Sunningdale power-sharing agreement of 1973, which included the Ulster Workers Council (UWC) strike that brought it down. The distinctions between the various groups was, to say the least, blurred in their own eyes.) But we do not know whether the GEN 47 decision ushered in intelligence assistance from the UDA to the British military, just as we do not know what, in general, the implications were of this Cabinet sub-committee meeting. It is beyond dispute, however, that when GEN 47 met at Downing Street, the UDA was capable of bringing many thousands of angry Loyalists on the streets of Belfast – and that political consideration, arguably, is what would have been foremost in the minds of ministers, soldiers and officials seated around the Cabinet table. After all, it was such people who kept Northern Ireland running for the British.

UDA LEADER DAVY PAYNE DOES THE MRF A BIG FAVOUR

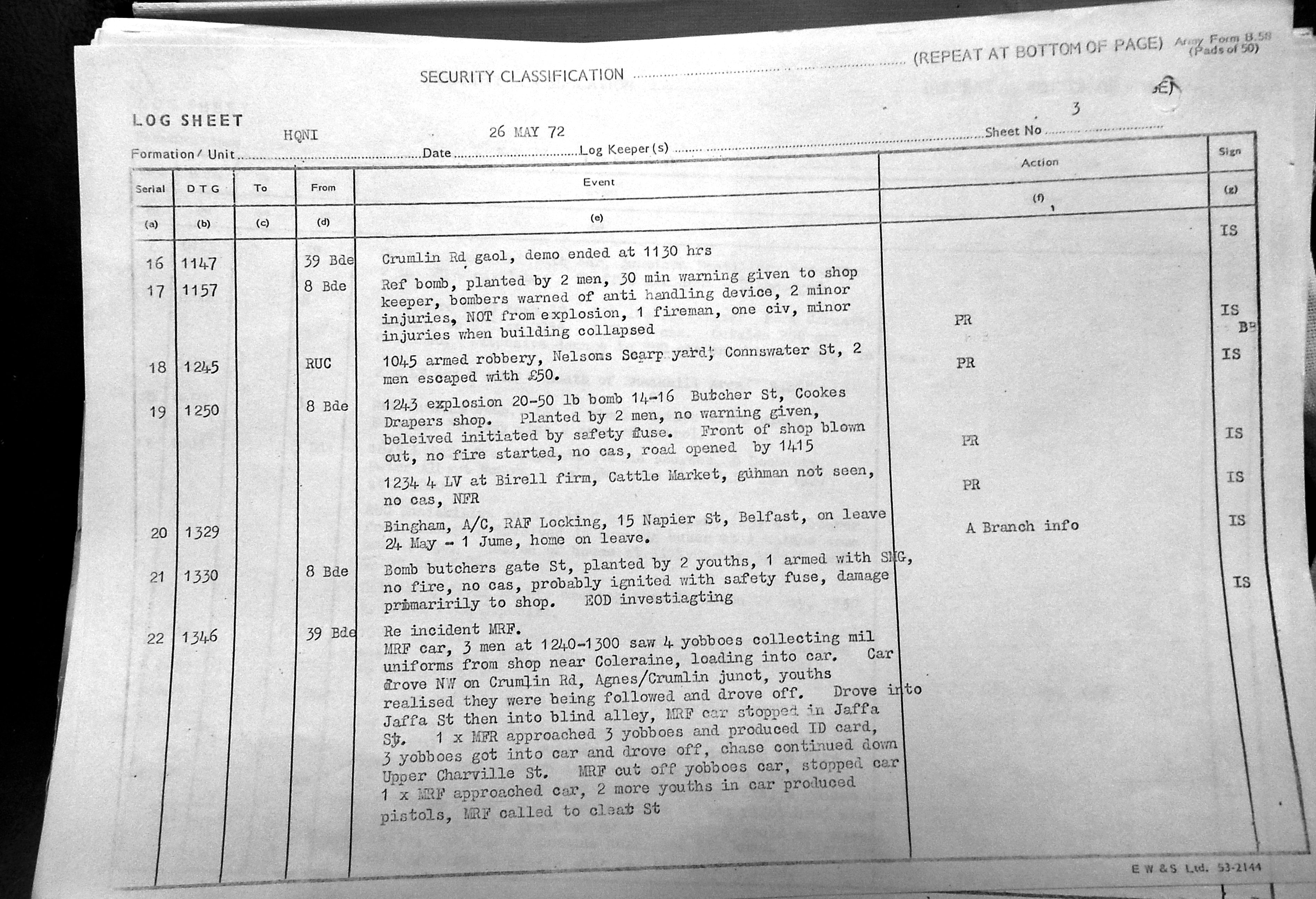

And there the matter may have rested except for the discovery of an intriguing set of British Army log sheets compiled over two days, May 26th and 27th, 1972 – eight months after that GEN 47 meeting at Downing Street – at two British Army control rooms, one at the headquarters of 39 Brigade in Belfast, and the other at British Army headquarters (HQNI) at Thiepval barracks in Lisburn, Co Antrim. The log sheets have been released into the public domain by the Kew archive.

General Frank Kitson, head of 39 Brigade in 1972 and believed to be architect of the Mobile Reaction Force. He was transferred to a post in the UK in April 1972, just before the events described in this post took place.

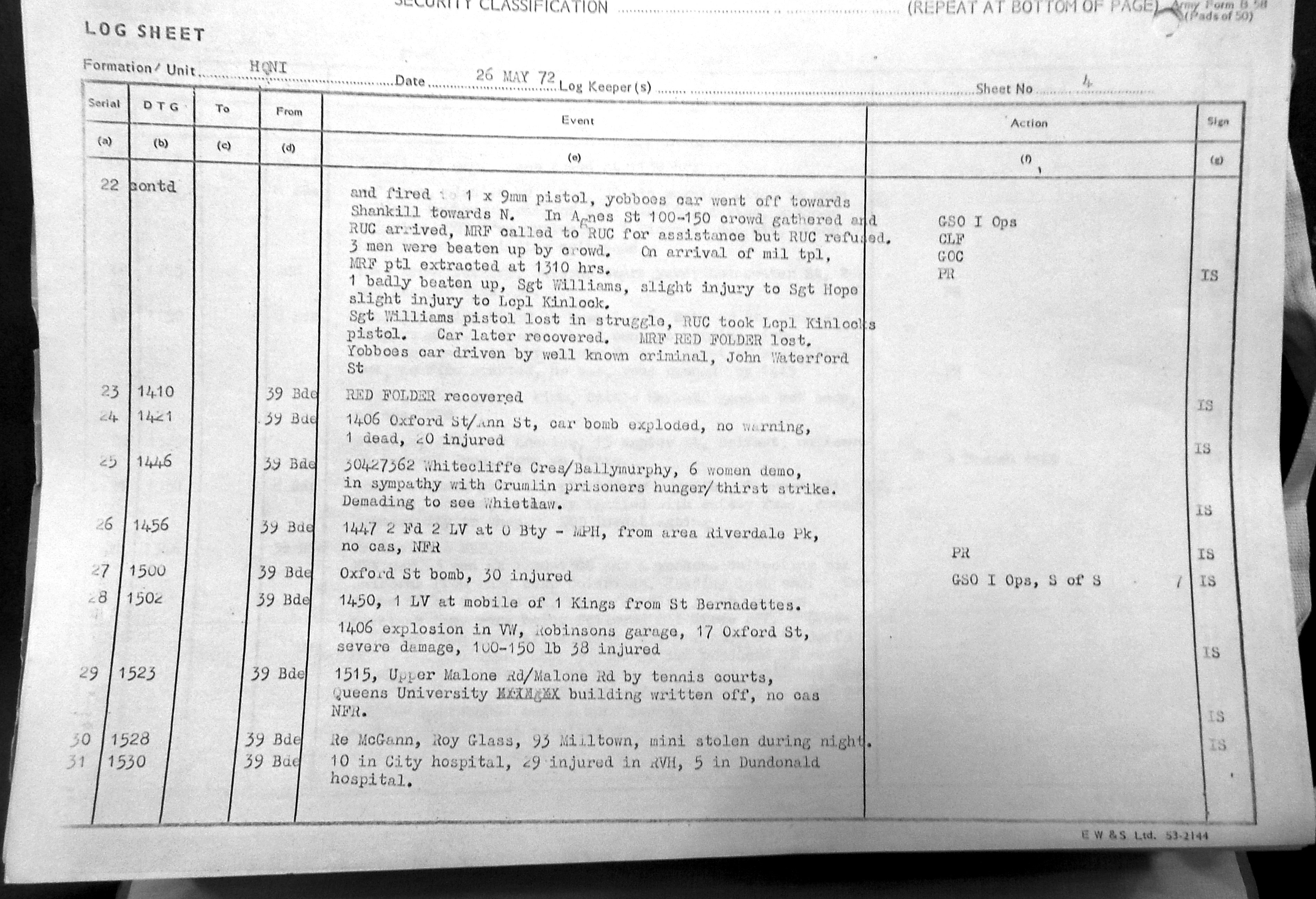

Both sets of log sheets describe a confrontation between a three-man, plain-clothes MRF unit – two sergeants and a lance-corporal – in a civilian car and a large Loyalist crowd on the Shankill Road which had mistaken the soldiers for IRA gunmen. It ended with the MRF team badly roughed up by an angry Loyalist crowd who also stole some of their equipment and classified paperwork, notably the MRF’s ‘Red Folder’ which contained detailed of the MRF’s personnel, code words, rendezvous points and so. The speed and efficiency with which the bulk of the stolen material was returned to the MRF and the role played in that retrieval by one of the Troubles most violent and notorious Loyalist paramilitary leaders – described in military reports as ‘a contact of the SF’ (Security Forces) – suggests that the GEN 47 proposal, or something like it, may have borne fruit. GEN 47 had raised the possibility that Protestant ‘vigilantes’ or ‘civil defence’ group could give intelligence ‘assistance’ to the British Army. Do the events described in these log sheets constitute the sort of ‘assistance’ envisaged? The various elements of this story will be referred to by their Serial numbers listed in the first column of the log sheets which are reproduced in chronological order below. First the log sheets compiled at HQNI, at Thiepval barracks, on the basis of information radioed in by Kitson’s 39 Brigade (It is interesting to note that in the Action column of the log sheets, the following very senior military personnel were informed about the incident: the officer in charge of Intelligence Operations, the Commander of Land Forces, the GOC, Sir Harry Tuzo and the Army’s public relations department. This was clearly a serious incident.) The account, dated May 26th, 1972, and beginning at 13:46, starts at Serial 22, and continues into the second log sheet. It describes how the motorised MRF patrol notices ‘4 yobboes’ loading military uniforms into a car and gave pursuit to the Crumlin Road/Shankill Road area. This account has the incident happening ‘near Coleraine’, which appears to be a mistake, possible caused by poor radio communications; other log sheets have the incident starting in Belfast city centre. The ‘yobboes’ car stops in Jaffa Street, the MRF approach it but it drives off again and heads to Upper Charleville Street. The MRF car cuts it off and when one of the soldiers approached the car, two of the ‘yobboes’ produced pistols and one of the MRF unit fires a single shot from his 9mm pistol. When a crowd of some 150 Loyalists then confront the MRF patrol the soldiers call the RUC for help but the police refuse to intervene. The three MRF soldiers are then beaten up by the crowd; Sgt Williams (who earlier played a major part in another controversial MRF operation) is badly injured, Sgt Hope and L Cpl Kinlock escape with slight injuries. But Sgt Williams has had his pistol taken and the MRF’s Red Folder is lost. This message is timed at 13:46. Just twenty-four minutes later, Serial 23, 39 Brigade informs HQNI that ‘RED FOLDER’ had been recovered. Just twelve minutes later, according to Serial 32, 39 Brigade tells Thiepval HQ that while Sgt Williams’ pistol is still missing, a ‘blue bag’, described as holding a ‘cosmetic outfit’ – presumably disguises – which was also stolen, is back in military possession along with the MRF’s ‘Red Folder’. Both the bag and the folder were ‘handed in by contact of SF’. SF presumably stands for security forces. So a contact of either the British Army or RUC recovered this valuable and secret document from the angry Loyalist crowd and ensured that it was returned to its proper owners. So who was this ‘contact of the SF (security forces)’? According to Serial 33, a message from 39 Brigade at 15:59, the ‘MRF folder, was lost for some time, handed to Flax St (British Army post) by David Payne 34 Brussell St associate of Frank Quigley’. (‘Brussell St’ is actually Brussels Street.)

The log sheets following these words were compiled in the control room of 39 Brigade and they describe, but in much greater detail, the incident as outlined in the HQNI log sheets reproduced above. They were based on messages transmitted by soldiers or units on the ground to 39 Brigade’s control room. For reasons probably due to poor radio reception, the location of the incident is misspelled as ‘Cargill’ or ‘Upper Cargill’ Street; the accurate location was Upper Charleville Street. Serial 32 gives 12:32 on May 26th as the starting point of the incident when a message is sent from the MRF patrol seeking assistance; ‘aggro developing’ is the terse report. Serial 35, a message from the MRF, says the undercover patrol spotted four men in a Ford Cortina buying a large quantity of ‘mil eqpt’ from a city centre store. They were followed onto the Shankill where one of the four was seen to produce a gun. ‘A chase started culminating in aggro in UPPER CARGILL ST’. Serial 41, a report from a patrol of soldiers from the Royal Regiment of Wales (RRW), said the MRF car had been recovered along with two of their three pistols. Serial 44, another report from RRW, said the MRF had opened fire and ‘Crowd of 150 being pacified. 3 mil men now out of car, negotiations in hand to recover car’. Serial 45 is a lengthy message to 39 Brigade from the MRF which adds significant detail to the account, including the contents of the MRF’s Red Folder. The message also notes that when the RUC arrived on the scene, they were less than helpful: ‘They were asked to assist, extricate the MRF men from the area but they allegedly refused’. The message continues:

The log sheets following these words were compiled in the control room of 39 Brigade and they describe, but in much greater detail, the incident as outlined in the HQNI log sheets reproduced above. They were based on messages transmitted by soldiers or units on the ground to 39 Brigade’s control room. For reasons probably due to poor radio reception, the location of the incident is misspelled as ‘Cargill’ or ‘Upper Cargill’ Street; the accurate location was Upper Charleville Street. Serial 32 gives 12:32 on May 26th as the starting point of the incident when a message is sent from the MRF patrol seeking assistance; ‘aggro developing’ is the terse report. Serial 35, a message from the MRF, says the undercover patrol spotted four men in a Ford Cortina buying a large quantity of ‘mil eqpt’ from a city centre store. They were followed onto the Shankill where one of the four was seen to produce a gun. ‘A chase started culminating in aggro in UPPER CARGILL ST’. Serial 41, a report from a patrol of soldiers from the Royal Regiment of Wales (RRW), said the MRF car had been recovered along with two of their three pistols. Serial 44, another report from RRW, said the MRF had opened fire and ‘Crowd of 150 being pacified. 3 mil men now out of car, negotiations in hand to recover car’. Serial 45 is a lengthy message to 39 Brigade from the MRF which adds significant detail to the account, including the contents of the MRF’s Red Folder. The message also notes that when the RUC arrived on the scene, they were less than helpful: ‘They were asked to assist, extricate the MRF men from the area but they allegedly refused’. The message continues:

The MRF men were then kicked and punched by the Prot crowd. Mil ptl then arrived and managed to get the 3 MRF men out. They were taken to Flax St (one badly beaten up, two slightly inured) One wpn lost (Sgt Williams’ 9mm pistol) in the crowd and the RUC took possession of Lcpl Kinlock’s 9 mm pistol. By the time the car was recovered the red folder (which contains nominal role, codes, c/s, RV’s in city registered initials etc) was missing.

Serial 46, a message from the RUC to 39 Brigade, adds more detail of the incident and ends with this revealing addition:

‘Special branch are investigating the loss of both pistol and folder and will contact Prot friends’.

Just two minutes later, at 13:52, too soon for the RUC to have contacted their ‘Prot friends’, the RRW contacts 39 Brigade with the message that the blue bag and red folder lost by the MRF have been recovered and were ‘handed over by Mr Davis a local contact in Shankill’, who offered to try to recover the missing MRF pistol. ‘Mr Davis’ seems to be a misspelling/mishearing of Davy Payne. Serial 56 is a detailed report from RRW outlining their role in the rescue of the three MRF soldiers.

The following day, May 27th, 1972, 39 Brigade had two entries concerning the previous day’s drama on the Shankill, both from RRW based in Flax Street in Ardoyne. Serial 59 reads:

The following day, May 27th, 1972, 39 Brigade had two entries concerning the previous day’s drama on the Shankill, both from RRW based in Flax Street in Ardoyne. Serial 59 reads:

Sgt Williams was found in the car badly beaten when sub-unit arrived. He was asked if there was anything important in the car he replied “the radio”. This was taken but no mention made of bag and its contents.

Serial 83 sees the RRW clearing up any confusion about who handed in the MRF bag and red folder to the military at Flax Street. An earlier message had named him as ‘Mr Davis’ but this message sets the record straight, although the surname is misspelt:

ref MRF incident – name of person who handed in the folder – Mr DAVID PANE of 34 Brussel Street. Under the heading Action, HQNI added: ‘Suspected UVF, member of SPC. Associate of Frank Quigley.

So, eight months after the British cabinet decided that Loyalist vigilante groups could not only be tolerated but ‘might be allowed to assist the Army with intelligence’, a known member of the UVF helps the MRF, the most secret military unit deployed against the IRA at the time, to recover secret documents and equipment lost in the course of a botched operation. HQNI, i.e. Thiepval barracks mistakenly described Payne as a member of the UVF, which he had been until the UDA appeared on the scene. By May, 1972 Payne was a senior member of the UDA in North Belfast. Not only that but Davy Payne is clearly not a walk-in; he was described in log sheets variously as ‘a contact of the SF’ (security forces) and ‘a local contact in Shankill’ by the Royal Regiment of Wales, while the RUC Special Branch assures Brigadier Kitson that they ‘…..are investigating the loss of both pistol and folder and will contact Prot friends’. Was Payne one of those friends?

So, eight months after the British cabinet decided that Loyalist vigilante groups could not only be tolerated but ‘might be allowed to assist the Army with intelligence’, a known member of the UVF helps the MRF, the most secret military unit deployed against the IRA at the time, to recover secret documents and equipment lost in the course of a botched operation. HQNI, i.e. Thiepval barracks mistakenly described Payne as a member of the UVF, which he had been until the UDA appeared on the scene. By May, 1972 Payne was a senior member of the UDA in North Belfast. Not only that but Davy Payne is clearly not a walk-in; he was described in log sheets variously as ‘a contact of the SF’ (security forces) and ‘a local contact in Shankill’ by the Royal Regiment of Wales, while the RUC Special Branch assures Brigadier Kitson that they ‘…..are investigating the loss of both pistol and folder and will contact Prot friends’. Was Payne one of those friends?

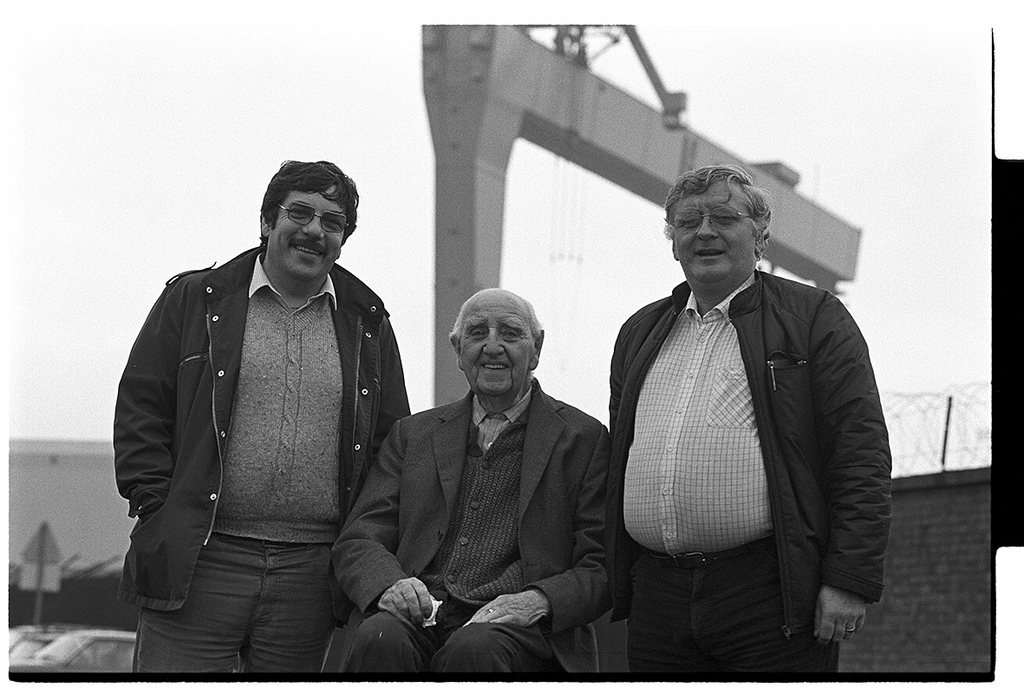

UDA leader Davy Payne in a photograph taken in the 1970’s when his killing spree was at its peak

It is worth noting that the apparent relationship between the RRW and Davy Payne could fall into the ‘purely unofficial and essentially local basis’ for intelligence co-operation between the military of Loyalist ‘vigilantes’ prescribed by Ted Heath’s Gen 47 meeting of the previous October. So who was this Davy Payne? Those in the media who had the job of covering his activities as a Loyalist paramilitary activist knew him to be one of the most violent and psychopathic killers to tread Northern Ireland’s violent stage during the Troubles. He began his paramilitary life as an early member of the UVF and after the arrest and jailing of Gusty Spence for the 1966 Malvern Street murders he went with the rest of the organisation into Tara, the bizarre Loyalist ‘doomsday’ outfit led by William McGrath, an evangelical leader and notorious pedophile who was later jailed for abusing boys at the Kincora home where he was a warden. When, in September/October 1971, the UVF left Tara, allegedly when McGrath asked it to murder a rival in the group, Payne left with them. The UDA emerged publicly in September 1971 and some time after that he joined the UDA and rose through the ranks, earning a place on its inner council and the rank of North Belfast brigadier. When Davy Payne died in 2003, Irish Times diarist, Kevin Myers penned this memorable profile of the UDA killer. The article describes in disturbing detail how Payne murdered two Catholics stopped at random on the Shankill road. One was the singer, Rosemary McCartney, the other was her boyfriend, Patrick O’Neill. They were killed on July 22nd, 1972, barely two months after the same Davy Payne had returned the MRF’s missing documents and equipment to the unit’s presumably grateful commanders, in an act of ‘intelligence’ co-operation very possibly enabled a few months earlier by Ted Heath’s GEN 47 cabinet committee:

A few days ago, a certain gentleman made a discovery of interest to us all: whether or not the devil exists. For last Wednesday the loyalist terrorist Davy Payne was buried. He was a uniquely evil man, and if I could have done anything to hasten his end, frankly, I would have. Payne was the beast from hell, and the sooner he was returned to his natural homeland, the better.

An older Davy Payne poses with UDA Supreme Commander, Andy Tyrie

Payne was one of the earliest members of the Ulster Defence Association, when it was still a rabble, with its masks and combat jackets and ludicrous semi-military titles: one in 10 of its members seemed to be brigadiers, and one in three were “lootenant colonels” (so much for what they understood of “Britishness”). Curiously, almost none were corporals or privates.

What Payne brought to this lumpen, clownish rabble was his astonishing readiness to kill. For most people, the taking of human life involves crossing a threshold of some kind or other. Not Payne. And it says something about the culture of violent loyalism that this creature rapidly became esteemed solely because of his unhesitating willingness to take human life.

The security policies of the British and Stormont Governments of the time – 1971-72 – in effect allowed Payne to roam free North and West Belfast, finding his victims; and he found them in large numbers. He is said to have invented the term “Romper Room” (after a children’s television programme of the time) to describe places where Catholics would be beaten before being murdered. Thus the term “romper”, to give a severe beating, entered the diseased argot of the Troubles.

In July 1972, a UDA roadblock – operating quite openly, and tolerated by the authorities in a quite scandalous and delinquent dereliction of their moral and legal duty – stopped a car carrying a young Catholic couple, Rose McCartney and Patrick O’Neill through the Shankill area. Rose was from the Falls, he from Ardoyne, and they were taking a shortcut through a loyalist area. Like so many Catholics who did so, they were to pay for their imprudence with their lives.

The UDA men took them to one of their headquarters, where they were separated. Patrick was beaten and burnt with cigarette-ends. Rose was merely questioned. The man supervising both interrogations was Davy Payne. He was masked, so they couldn’t have identified him.

A victim of a Loyalist death squad found dumped in an alleyway

Patrick had a reputation for being something of a messer, but his conduct during his final ordeal was, I’m told, extremely dignified. Rose was asked to identify any IRA men in Iris Street, where she lived. She said she didn’t know any. But the UDA was aware that a prominent IRA man lived a couple of doors away from her.

The UDA had found a membership card for a traditional music club in her bag. Payne was fascinated. Was she really a singer, he asked. She was, aye. Prove it, he said. Go on prove it. How, she asked. By singing, he said.

I don’t know what song she sang: but the last song I’d heard her sing was My Lagan Love, just the week before in her club. Maybe she sang that. The loyalists solemnly sat around in their masks, listening to her. They liked her voice and congratulated her on it. But it didn’t save her. Payne was the UDA commander in the area, and he insisted that she die, firstly because she hadn’t named the local IRA man, and secondly, because he’d never killed a woman.

They brought Paddy and Rose together. Both were blindfolded. They were offered a cigarette each, and they lit up. Rose reached over and touched Paddy’s hand, which had been broken during torture. He recoiled. “Did they hurt you?” she cried. “No,” he lied, “I didn’t want you to burn yourself on my cigarette.” The two were put into the back seat of a car, and Payne shot them both. Other UDA men involved in the interrogation then took turns to shoot them, both for the honour of killing a woman, and also to bind them all into the one conspiracy. One of that number later told me about the events of the night.

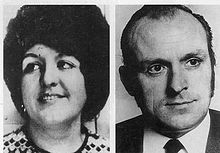

Rose wasn’t the last woman Payne killed. A year later he and Johnny White came across SDLP Senator Paddy Wilson and his Protestant girlfriend Irene Andrews in his parked car on the Hightown Road in North Belfast. The UDA men went berserk, stabbing Paddy 32 times, and Irene 16. Over the coming years, White and Payne were repeatedly questioned by the police about these killings. One day White cracked and confessed, but Payne never did.

Irene Andrews and Paddy Wilson – stabbed to death by Davy Payne

At about this time, I was visiting a garage owned by Joe, a Protestant convert to Catholicism – a deadly crime in loyalist eyes. He told me that a suspicious car had been cruising around, and was now parked up the road. I checked it, and sitting inside was Davy Payne. I told him I hoped he wasn’t targeting Joe. He asked me what the f— I was doing, messing around with a Protestant who’d thrown in his lot with the Taigs? Getting my car fixed, I told him. And now that I’d seen him, Davy Payne, checking Joe out, I said, he clearly couldn’t kill him.

“Mebbe not,” he sniffed. He slid his spectacles down on to the bridge of his nose, and peered menacingly over the rim at me – a characteristic gesture of his.

“You know, I’ve never killed a journalist. Not yet, anyway.” And now you won’t.

Davy Payne often liked to torture his victims before killing them. His specialty was to give victims repeated electrical shocks via a box-shaped device he had acquired from which wires ran attached to electrodes. These would be fixed to sensitive parts of the victim’s body and a current created by turning a handle on the box. Payne rose to leadership of the UDA in North Belfast where one of his underlings was Brian Nelson, who later gained notoriety as the UDA’s intelligence chief and spy for the British Army’s agent-running body in Northern Ireland, the Force Research Unit (FRU).

Brian Nelson

In 1973, Nelson was arrested along with two other UDA members as they were bundling a Catholic man, Gerry Higgins into a car and to an almost certain death. Higgins had been kidnapped earlier that day and tortured in a local drinking club; he was probably being taken away to be shot when he was saved. It is believed that a device similar to Payne’s electrical box was used on him. Payne himself may even have been involved in the torture. As Nelson and his colleagues struggled with Higgins they were spotted by a passing patrol from the Light Infantry, then under the command of the Coldstream Guards regiment, who rescued him and arrested Nelson and his colleagues. Before he was handed over to the RUC for processing and eventual trial, Nelson was held in military custody and interrogated by an intelligence officer from the Coldstream Guards, a Captain Anthony Pollen, who was shot dead by the IRA in Derry, a year or so later. This unusual procedure was sanctioned by no less than the leadership of 39 Brigade. When Nelson had served his jail term, he rejoined the UDA on the instructions of the Force Research Unit and became one of the most controversial double agents run by the British Army during the Troubles. CONCLUSION: SOME QUESTIONS AND OBSERVATIONS We don’t know if the proposal for an intelligence-based relationship between Loyalist/Protestant ‘vigilante’ groups and the British security forces, as suggested by Ted Heath’s Cabinet committee, GEN 47, in October 1971, was actually put in place. But we do now have compelling evidence that in principle a relationship with Loyalist ‘civil defence groups’ or ‘vigilantes’, centered on intelligence, was suggested and approved at the highest level of the British government. GEN 47 said ‘vigilante’ type groups could be tolerated, and they were. The UDA for instance was not proscribed until 1992 but its fictional armed wing, the Ulster Freedom Fighters, was, even though it never existed except on paper, something that would have been well known to the police and army. The only other group from this period that was banned was the Red Hand Commando, which was linked to the UVF, which had been outlawed in the 1960’s. We do not know what the intelligence assistance referred to in GEN 47 meant or was intended to mean. Was it a one-sided relationship or was there give and take on both sides? What sort of intelligence would have been involved? How was the relationship organised and run? Would such activity be confined to information or were other intelligence operations, such as dirty tricks involved? GEN 47 implicitly envisaged the intelligence assistance to be a one-way street, i.e. from Loyalist vigilantes to the British Army. Was this realistic? In practice would this arrangement only be workable if the flow of information went in both directions? Did Davy Payne’s retrieval of MRF documents and equipment constitute evidence that the GEN 47 decision had not only been implemented but that it authorised British Army dealings with killers? Did Payne’s retrieval of the MRF’s red bag constitute the sort of ‘intelligence assistance’ contemplated by GEN 47? Or was Payne merely looking after his own interests when he returned the MRF material, building up brownie points with people who one day might try to put him behind bars, or worse? Why did the British Army describe Payne as ‘a contact of the SF’ (security forces)? If groups like the UDA, and their close cousins the UVF, were excluded, then which groups were part of this arrangement? And what precautions were taken to ensure that sensitive intelligence stayed within those groups and did not leak? Why did the leadership of 39 Brigade authorise an intelligence officer from the Coldstream Guards to question Brian Nelson after his arrest, out of sight and sound of the RUC? What was the relationship between Davy Payne, Brian Nelson and the British Army? Finally, the most serious and disturbing question of all. Is GEN 47 the moment when collusion began between the British and Loyalists in Northern Ireland? All these questions require answers.

Fascinating reading. Thanks for this. A hell of a lot to digest here.

As an aside, the photograph of the”…victim of a Loyalist death squad found dumped in an alleyway” is Joseph Donegan, who was murdered by Lennie Murphy and Tommy Stewart in October 1982.

Detailed, forensic work that may prove of great importance as the history of this period is slowly recovered from cultivated obscurity. Well done.

Investigative journalism is still alive, despite the best efforts of its enemies.

The notion that Payne was a British asset conflicts with the fact that seven months after the MRF incident, the 29th of December, he was arrested following a search of a lock-up garage owned by him, where they found five stolen SLRs, a Schmeisser submachine-gun, a revolver, plus ammunition and parts for homemade guns. Crucially, this was a joint RUC/army operation (3rd Battalion Light Infantry). The case went to trial, but juries still existed at this point and Payne was acquitted after the prosecution failed to convince them that he would be the only one with access to the garage. It goes without saying that a Diplock court would have convicted him. As it was he was then detained without trial under the Special Powers Act, for a year I think.

This is an argument for full and independent access to the files which exist in numerous British government intelligence dumps scattered around England. I don’t think I suggested Payne was an ‘asset’ of BMI just that the juxtaposition of events, viz. Tuzo’s suggestion of an intelligence relationship with Protestant ‘defense’ groups and Payne’s favour to the MRF begged the obvious questions. We need to know more about this episode and the info is in the files, somewhere, Like Chicksand for e.g.

Incidentally, what better way to give cover to a double agent than to charge him with something that has enough holes in it to ensure an acquittal followed by a short period as an internee? All calculated to dismiss suspicions or at least undermine them sufficiently to allow Mr Payne to resume long term value as an informant. Of course, that shows my suspicious bent of mind but it is how such things can be managed.

Pingback: The MRF File – Part Six: Blood On The Streets, The MRF Goes To War | The Broken Elbow

Pingback: The MRF File – Davy Payne, Frank Quigley And The MRF – A Mystery Solved | The Broken Elbow

This is footage (I think) of the arms find: https://tinyurl.com/armsfind291272

(you need to register with the BBC for access to the link above)