Partly in a search for refuge from the never-ending COVID crisis I have been reading Thomas Leahy’s thesis, submitted to King’s College London and now published as a book, arguing, or rather attempting to argue, that the Provisional’s embrace of the peace process had little or nothing to do with the fact that British spies had so undermined the IRA that military methods had become redundant, leaving politics as the sole alternative.

Incidentally you can read the thesis yourself here, or read The Irish News’ story which summarises his thesis. Now a lecturer at Cardiff University, his book can be purchased here.

Regular readers of thebrokenelbow.com will know, or suspect at least, that not only do I not think this theory holds water but it is in key ways the wrong issue to raise or question to ask.

The question might be reversed to make more sense, asking did the long-held and cautiously nurtured ambitions of Sinn Fein leaders to take a political road encourage a less than chary approach to attempts by British intelligence to infiltrate and shape the IRA? A subsidiary question is whether this was due to carelessness or intent?

Whatever the answers to those questions, I do know that by the early 1990’s, just a few years away from the first ceasefire, British intelligence’s own assessment was that one out of every three IRA members was working either for MI5, the FRU or RUC Special Branch, that 80 per cent of IRA operations were being interdicted and that the British had two agents working at the highest levels of the IRA, one of them being the Head of Internal Security, Freddie Scappaticci.

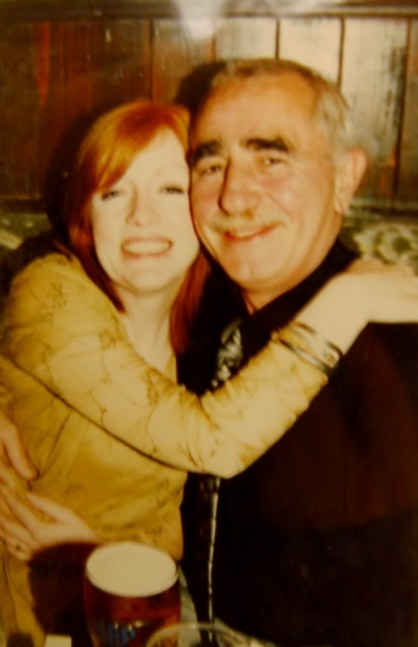

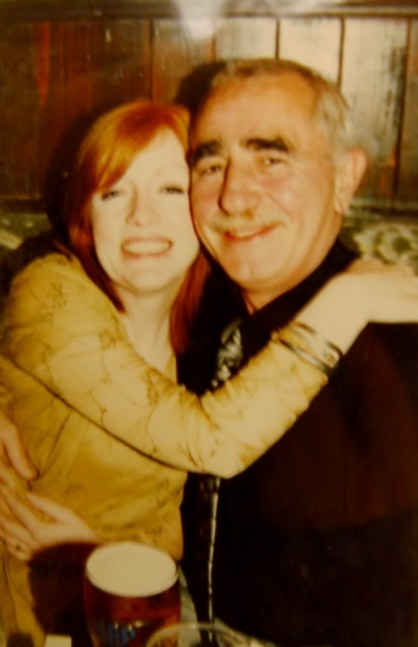

Dolours Price and Brendan Hughes

So myself and Dr Leahy would be at different ends of this debate and having read about half of his thesis I find nothing in what he has written so far, to change my mind over the central issue, which is that after 1972, the British gradually pushed the IRA onto the back foot, not least by intelligence methods.

But that is not what prompted this post.

Dr Leahy cites my books, ‘A Secret History of the IRA‘ and ‘Voices From The Grave‘ repeatedly in his thesis which is flattering but also puzzling since he never once contacted me to ask follow up questions or to probe certain incidents in greater depth. I have always been happy to assist researchers and my door would have been open to him. And it is invariably the case that there are details of some incidents that the writer cannot, for a variety of reasons, describe when they would have liked to.

But he never knocked at my door nor came near it, as far as I know.

One incident stands out as deficient in this respect and that was the 1973 IRA bombing of London, led by the Price sisters and timed to coincide with the first and only Border referendum held in Northern Ireland.

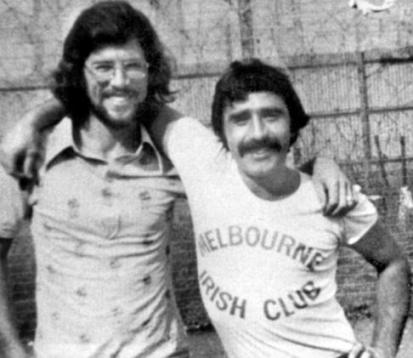

George Poyntz – became a Garda spy on the IRA by accident when he was mistaken by the IRA as a sympathiser. He realised he could make money selling IRA secrets to the police. He betrayed the London bombers to the RUC Special Branch in 1973

Dr Leahy acknowledges that the Old Bailey bombing, as it was known in the Fleet Street press, was interdicted thanks to an IRA informer whom his RUC Special Branch handler, Chief Superintendent George Clarke in his fascinating account of his life in the police, dubbed ‘MacMahon’, but who was really George Poyntz, one of the most remarkable and enigmatic British spies produced by the Troubles.

This is how he describes the incident:

The English campaign, however, started disastrously. On 8 March 1973, 200 people were injured and one person died after two car bombs exploded, including outside the Old Bailey. Other bombs were defused. A number of Provisionals were arrested when attempting to fly back to Ireland on the same day. In November 1973, nine people were found guilty of the bombings, including Gerry Kelly, today a senior Sinn Féin MLA, and Marian and Dolours Price, prominent dissenting republicans in recent years. There has always been suspicion that a high-level informer leaked details of the operation, since the police sealed the borders before the attacks.

In 2009, these suspicions were somewhat vindicated by the release of George Clarke’s account. Clarke alleges that information was provided by a senior Provisional, whom he describes as being involved since the 1950s. This individual is alleged to have trained volunteers, offered safe houses and supplies from county Louth. His close association with senior IRA leaders apparently meant that this informer, ‘McMahon’, knew about the London bombings in March 1973. Clarke says that McMahon’s information alerted the mainland police and set-up the arrests. The risk for McMahon was that few people knew about the proposed attacks, which could have placed suspicion on him. Yet no suspicion arose, presumably because other senior Belfast personnel, such as Brendan Hughes, did not believe spies were involved. Instead, Hughes felt ‘the simple mistake we made was that we tried to get the people out of England too quickly’.

Hughes does make a valid point. In future, IRA bombing teams in London were not pulled-out immediately and remained as ‘sleeper’ units, hiding across England. The volunteers involved in March 1973 mostly came from Belfast too, which made the risk of exposure greater. If one became known, others could be discovered simply via the intelligence services investigating who they associated with. Kelly, in particular, was a ‘red light’, a volunteer already on-the-run, making his disappearance from the area suspicious.

Had he bothered to make contact I would have given him more detail of the British interdiction of the Old Bailey bombing that would have shed light on, or at least posed more questions about the extent of British intelligence penetration of the IRA at this relatively early stage of the Troubles.

The story was told to me by Dolours Price back when we were filming ‘Voices From The Grave‘ in Dublin for RTE but I was not free to talk about it until after her untimely death in 2013, some two years before Dr Leahy delivered his thesis to his academic superiors at King’s College .

Her story went like this: shortly after she and all but one of the bombing team were arrested at Heathrow airport – the ‘one’ being in the airport loo when the police swooped – she was taken to a police station in London for questioning.

When she arrived she saw the headline in the evening paper on a desk: ‘IRA Plans Four Car Bombs‘ in London or words to that effect.

The plan to bomb London, which had been overseen by Belfast Commander Gerry Adams and organised by the Belfast intelligence chief, Pat McClure had envisaged six car bombs.

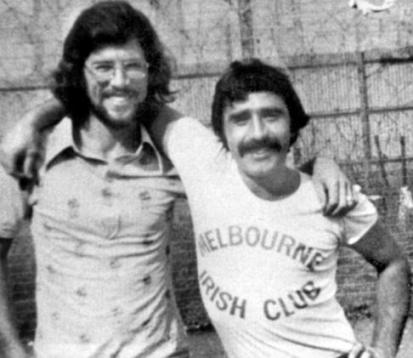

Gerry Adams and Brendan Hughes, pictured when both were interned at Long Kesh, circa 1974, a year after the Old Bailey bombing

The cars to be used were stolen some weeks before the plan was to be enacted, the plates changed and the vehicles resprayed. The work was done by George Poyntz at his Border garage near the Co Monaghan border.

When, the night before the bombing, Poyntz, who had worked for the Garda Special Branch during the 1956-62 Border campaign, offered his services to the RUC Special Branch, he believed that six IRA car bombs would be ferried to the British capital.

But when the cars were being loaded on to the Liverpool Ferry at Belfast docks, the police gave the fourth car a more than usually intense inspection. Dolours Price, who led the operation, decided not to push her luck and ordered the fifth and sixth cars to remain in Belfast.

Later she made a phone call to a number in Belfast and left the message: ‘Tell him it will be four’. ‘Him’ was Gerry Adams of course and this was Dolours Price’s way of telling the IRA chief that there would be four car bombs in London not the planned six.

There is no way that George Poyntz would have known this.

The headline in the evening paper that she saw in the police station after her arrest was based on a Scotland Yard briefing. So the security authorities must have received this information from elsewhere.

Either a human source separate from George Poyntz, someone with access to Gerry Adams, had passed on the information, or the phone used by the IRA leadership had been bugged by the British.

Either way the British had infiltrated the IRA close and high enough to interdict messages sent to its then Belfast commander. As penetration of an enemy’s secrets goes, that is undeniably pretty impressive.

Had Dr Leahy contacted me, I would happily have shared this story with him, even if it demonstrated that British penetration of the IRA was deeper and more extensive than he maybe would have liked to hear.

You must be logged in to post a comment.